Supply disruptions, drought in China, and rebounding electricity demand have increased the demand for coal and raised its prices. Since the start of the year, the price of high energy Australian coal—the benchmark for the Asian market—increased 86 percent to above $150 a metric ton—its highest level since September 2008. In South Africa, coal is trading at its highest level in more than 10 years, increasing 44 percent in 2021. In the energy arena, only Brent crude has similar increases having risen 44 percent. Despite renewable energy (wind and solar) increasing their capacity rapidly, they cannot keep up with the increasing global demand for electricity, which fossil fuels are filling.

Price increases have been primarily driven by robust demand from China, with Chinese buyers willing to secure coal at the highest prices. A drought earlier this year in southern China, which knocked out hydroelectric dams and boosted demand for coal, played a significant role. China has struggled to boost domestic coal supply to meet increased demand for electricity generation as its economy continues to recover from the pandemic because of tough safety rules. Coal production in Indonesia, China’s biggest overseas coal supplier, has been hampered by rain, while rail and port constraints have affected shipments from Russia and South Africa. China’s ban on Australian coal—implemented after Australia raised questions about the potential Chinese source of Covid-19—eliminated purchases from that country. Surging natural gas prices prompted some utility companies in Japan and Europe to switch to coal, further tightening the market.

New Zealand

Even New Zealand is importing large amounts of coal as lower than normal rainfall in recent years has hampered hydropower generation, which is the country’s largest source of renewable electricity, and as its natural gas supply has dropped from 13 percent in 2019 to 11 percent in the first quarter of this year. In 2019, hydropower contributed 58 percent of the country’s electricity supply, compared to 52.5 percent in the first quarter of 2021.

The government expects an additional 150,000 metric tons of coal will be imported—a 14 percent increase on last year’s total, which was over 1 million metric tons. Coal accounted for more than 10 percent of the country’s electricity in the first three months of this year, while five years ago it was just 2 percent. Last year, New Zealand used approximately 800,000 metric tons of coal to generate electricity, while over half that (427,000 metric tons) were used to produce electricity in the first quarter of this year—the most in 14 years.

The share of renewable electricity is high in New Zealand, at about 80 percent—the same level since the mid-1970s. Wind and geothermal generation have increased from 7 percent to 23 percent of the country’s total electricity generation in the past two decades.

Electricity Demand

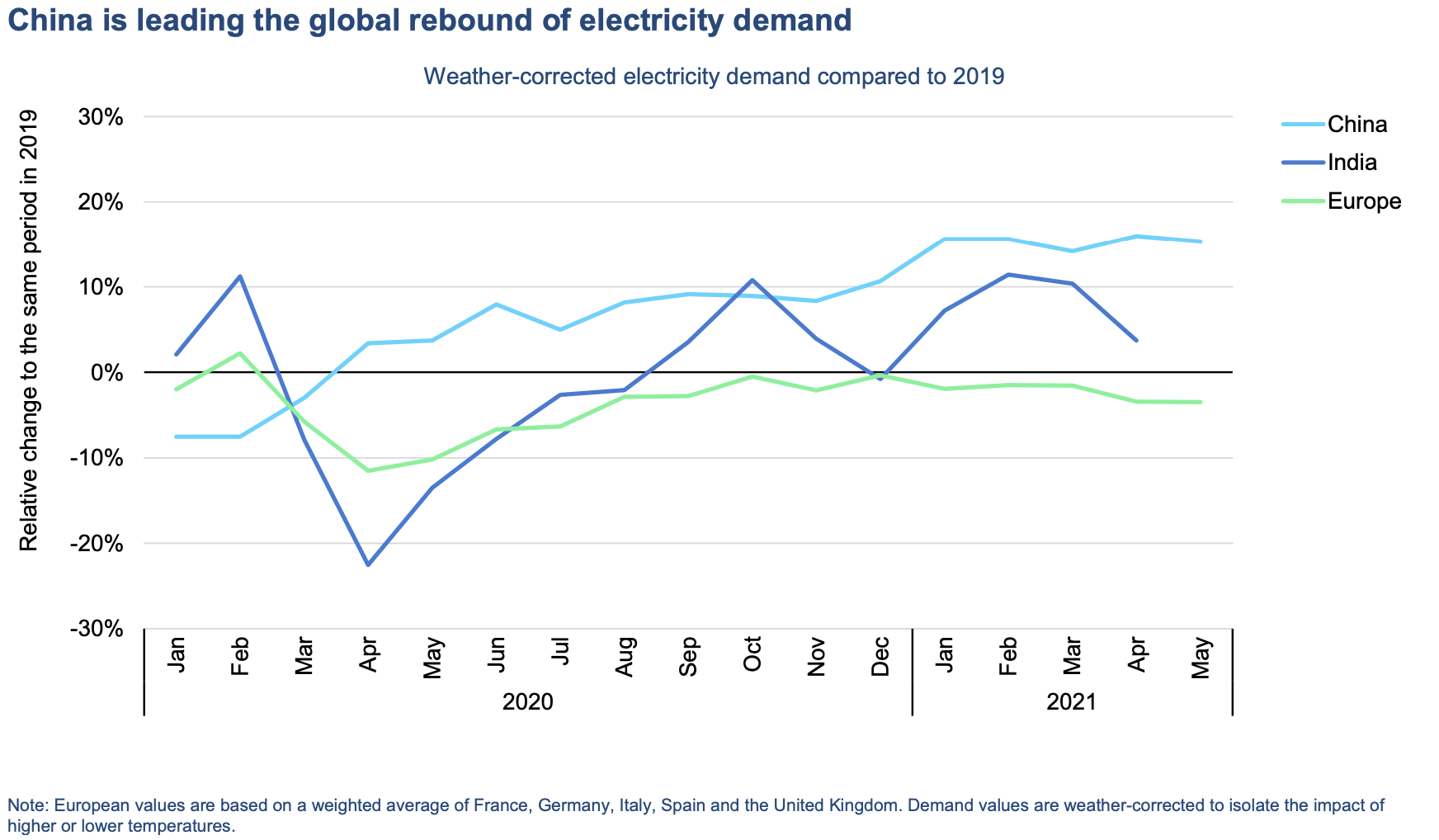

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global electricity demand is expected to grow close to 5 percent in 2021 and 4 percent in 2022, increasing from its decline of almost 1 percent in 2020. IEA in its Electricity Market Report expects renewable energy only to produce around half of the net electricity demand increase in 2021 and 2022. IEA expects that fossil fuel-based electricity to cover 45 percent of additional demand in 2021 and 40 percent in 2022. As a result, IEA predicts coal-fired electricity to increase almost 5 percent this year, exceeding pre-pandemic levels, and to grow a further 3 percent in 2022, when it could reach a record high. More than half of global growth in 2022 is expected to occur in China, the world’s largest electricity consumer. India, the third-largest consumer, is expected to account for 9 percent of global growth.

It is not clear whether high coal prices will continue as China is expected to release coal from its strategic stockpiles and order miners to increase production. China plans to add nearly 110 million metric tons per annum of advanced coal production capacity in the second half of 2021, having added more than 140 million metric tons per annum of coal mining capacity in the first half of this year. Also, contributing to a lower outlook for coal prices is that fossil power generation in China typically hits its highest level in July and August and then declines. Global coal demand could weaken in the future as environmental policies result in banks and insurers refusing to fund new projects. However, it is likely that China and India will continue to buy coal in the export market for the next decade or so.

G20 Communique

With coal use surging, it is no wonder that energy and environment ministers from the Group of 20 nations failed to agree on the wording of key climate change commitments in their final communique from their recent meeting. China and India declined to sign regarding two contested points: phasing out coal power, which most countries wanted to achieve by 2025, and the other concerning wording surrounding a 1.5-2 degree Celsius limit on projected global temperature increases that was set by the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Conclusion

Coal prices are at their highest level since 2008 despite countries wanting to phase coal out as part of the path to reaching the Paris Climate agreement of 2015. While many countries are increasing their coal use in 2021 and 2022, China is expected to represent about half of that expected increase. Coal use is increasing because renewable energy cannot supply the increase in electricity demand expected as coronavirus lockdowns are lifted. In fact, renewable energy (wind and solar power) are only expected to meet about half of the increase expected in electricity generation. The importance of coal to China and India can be seen in their refusal to sign the G20 communique that commits to phasing out coal.