I encourage everyone to read “The Simon Abundance Index: A New Way to Measure Availability of Resources,” a new paper by Gale L. Pooley of BYU and Marian L. Tupy of the Cato Institute. The paper addresses the contemporary debate on the impact of population on resource scarcity. In the paper, the authors explain new tools to measure the availability of resources by taking into account changes in per capita income and population over time.

Contemporary Debate Over Resource Scarcity

The modern debate over resource depletion began in the 1980s in a debate between biologist Paul Ehrlich and economist Julian Simon. Ehrlich feared that a growth in population would deplete natural resources; Simon counter-intuitively argued that population growth would actually make resources more abundant. Simon’s argument was based on the idea that human beings are the ultimate resource and that the depletionist view of resources ignored long-term changes in income as well as the impact that technology and human ingenuity would have on the availability of resources.

In September of 1980, Simon challenged Ehrlich to a bet on resource depletion. Simon told Ehrlich he could choose a group of raw materials that he thought would become less abundant over the next decade. If the real prices of those materials increased over that time, then Ehrlich would win the bet. In the period between September 1980 and September 1990, population rose by 873 million people, and all five commodities that Ehrlich selected declined in real price, with an average drop of 57.6 percent.

Despite the fact that Simon emerged victorious in the bet, this did not put an end to the public debate over resource scarcity and population growth. Supporters of Ehrlich correctly noted that, to some extent, Simon got lucky, because there are some examples of cases where if the bet had taken place during a different decade, Simon would have lost. Pooley and Tupy are responding to this argument by pointing out that a simple comparison in the changes in real prices over time is not the best measure of the impacts of population growth on resource availability; they have developed new tools that take into account other important factors, which I describe below.

Time-Price and Resources

The novelty of Pooley and Tupy’s paper is that it revisits this debate and reinterprets relative scarcity through the lens of the “time-price” of resources. This pricing mechanism takes into account the amount of time that people must spend working to earn enough money to purchase a particular resource. By using the time-price measure, the Ehrlich-Simon bet and contemporary arguments about overpopulation are brought into perspective. As the paper notes:

Considering the real average hourly income per capita rose by 80.1 percent, the time it took to earn enough money to buy one unit in our basket of commodities in 1980 bought 2.83 units in 2017.

This consideration is important because unlike resources, time cannot be made more abundant through greater efficiency, increases in supply, or decreases in demand. Therefore, time-price offers a deeper account of the material progress we have achieved as a lower time-price means people have to work less to earn enough money to purchase something.

Price Elasticity of Population

Another important insight of this paper is Pooley and Tupy’s development of the concept of the price elasticity of population (PEP). This concept offers richer insights into the effect of population growth on the availability of resources. The paper explains:

On the basis of a population increase of 69.3 percent and a time-price decline of 64.7 percent, we found that the time-price of our basket of commodities decline by 0.934 percent for every 1 percent increase in population. That means that every additional human being born on our planet seems to be making resources proportionately more plentiful for the rest of us.

This measure lends additional credence to Julian Simon’s argument that commodities grow more abundant in relation to population growth. The relationship between prices and innovation isn’t fixed. As long as people are operating within the framework of property rights, free exchange and the rule of law, an increase in the relative scarcity of a resource leads to a higher price, which in turn creates incentives for innovation.

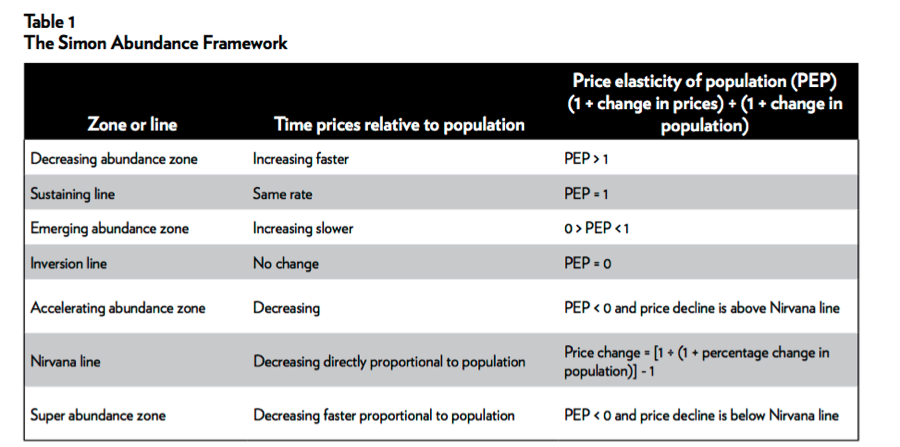

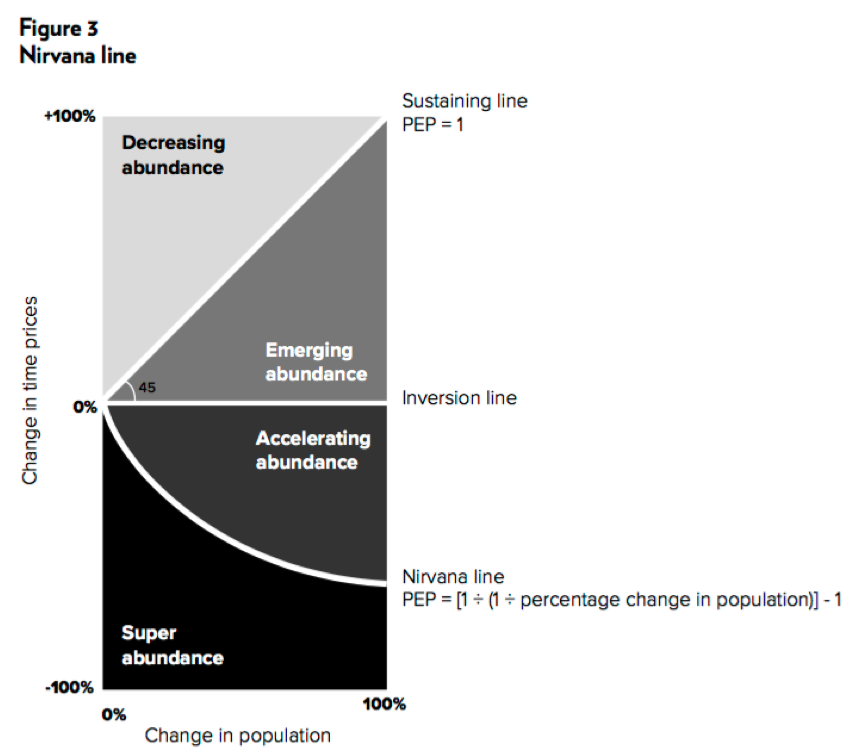

The Simon Abundance Framework

Pooley and Tupy combine these two measures to develop the Simon Abundance Framework. This framework contextualizes PEP values by establishing four zones to categorize resource abundance. The framework is explained in the chart and graph pictured below:

Simon’s Rule

The main takeaway from the paper is that Julian Simon was indeed correct in his explanation that an increase in population would lead to greater resource abundance and cheaper commodities. Additionally, it backs up Simon’s prediction that even in a world of super abundance, people still have a pessimistic view of our ability to make use of our resources. In recent years, arguments about overpopulation seem to be making a comeback, but Pooley and Tupy have put those concerns into perspective. They remind us that we live in a world defined by extreme abundance, a reality that is only made possible by the institutions of a free society.