Somehow I missed it when it first ran, but two years ago the Manhattan Institute’s Senior Fellow Oren Cass wrote a masterful critique of the typical arguments for a U.S. carbon tax. His essay, “The Carbon Tax Shell Game,” is so good that I’m going to spend two posts here at IER amplifying some of his strongest points. As I’ve been illustrating over the years with my own work (e.g., here and here), the case for a carbon tax falls apart once you start picking at it.

The Carbon Tax Is a Shell Game

First let’s establish what Cass means when he calls the arguments for a carbon tax a “shell game”:

Simply put, the carbon tax is a shell game. The range of designs, prices, rationales, and claimed benefits varies so widely — even within many individual arguments for the tax — that assessing the actual validity of most discrete proposals becomes nearly impossible. The insubstantial effect on emissions gets obscured by discussions of the fiscal benefits. The negative fiscal effects get offset by claims of environmental efficacy. The tax’s simplicity and practicality are touted, even as new complexity is introduced to address each flaw. The same revenues are rhetorically spent to achieve multiple ends, even as the different promises made to each constituency would be rejected by the others.

This is a point I’ve stressed repeatedly in my analyses for IER. For example, when proponents of a carbon tax pitch it to American conservatives and libertarians, they explain that if we have a revenue-neutral carbon tax where 100% of the proceeds are devoted to cutting taxes on capital, then reputable models show that this could boost even conventional economic growth, in addition to whatever environmental benefits accrue from reduced greenhouse gas emissions. This is called a “double dividend” that arises when policymakers began to “tax bads, not goods.”

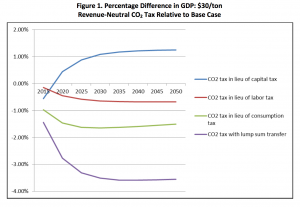

However, I want to stress that all of the revenues from the carbon tax need to go to tax cuts on capital in order for this to even work in theory. Here is a chart I took from a 2013 Resources for the Future (RFF) analysis:

https://www.instituteforenergyresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/RFF-Carbon-Tax-Swap.png

As the diagram indicates, the RFF model shows that only if carbon tax revenues were devoted entirely to a corporate income tax cut would the economy’s growth rise above the baseline. (That’s the blue line in Figure 1.)

In contrast, if all of the carbon tax receipts were used to do any of the following: (1) lower tax rates on workers (red line); (2) lower the tax rate on consumption (green line); or (3) give a lump-sum check pay to citizens (purple line), then—in all three of those alternative scenarios—the carbon tax, even though it was “revenue neutral” by design, would make economic output smaller than it otherwise would be. (To be clear, the RFF authors would still claim environmental benefits from the reduced emissions.)

Focus your attention on the purple line in Figure 1. This option is what people are popularly calling “carbon fee and dividend,” where the proceeds of a new carbon tax are simply mailed lump-sum back to citizens. This is touted as being very transparent, relative to other proposals (and I agree that it is).

However, the RFF study found that this type of “fee and dividend” approach would reduce GDP about 3.5 percent below what it otherwise would have been. In contrast, even the best-case scenario of a tax cut given entirely to corporations (blue line) would mean a GDP surplus of a little more than 1 percent above baseline.

Now, of course, there’s more to life than GDP statistics. But my point is that the people trying to sell conservatives and libertarians on the alleged “win-win” “double-dividend” scenarios are engaged in Oren Cass’s shell game. There is no way in the world that a massive new U.S. carbon tax is going to be implemented, in which all of the new revenues are devoted to cutting corporate income taxes.

Don’t Take Our Word For It

We can see that the “fashionable” proposals that are anywhere close to actual political proposals do not consist entirely of tax cuts on corporations. For example, the recent Whitehouse-Schatz proposal, unveiled at the American Enterprise Institute, is ostensibly revenue neutral. Furthermore, one of its features is a reduction in the corporate income tax rate from 35 to 29 percent. So far, this sounds like it’s a “pro-growth” measure, right?

But hold on. The Whitehouse-Schatz proposal would also use its revenues to fund a reduction in payroll taxes (but it is a flat $550 tax credit, so it lacks “supply-side” incentives and acts as a lump-sum check), and to allocate $10 billion annually in grants to states to assist low-income people who will be hit the hardest by higher energy prices.

Thus we see that the Whitehouse-Schatz proposal violates the promise of a “double-dividend” right out of the starting gate. These Democratic senators know full well that if they are going to propose a measure that increases the price of electricity and gasoline—which is the whole point of a carbon tax, since its purpose is to alter behavior—then they have to show that they are going to help average workers and especially poor households deal with the shock. There is no way someone could sell federal legislation that could be truthfully described as “forcing poor people to pay higher heating bills so that rich shareholders can get a $2 trillion tax cut.”

So we see one particular aspect of the shell game described by Cass: Proponents of a carbon tax can promise “pro-growth” corporate income tax cuts to conservative supply-siders, but when progressives worry about the impact on poor workers, the carbon tax people all of a sudden talk about how much revenue can be used to help them. Furthermore, carbon tax proponents entice environmentalists with promises of R&D funding for “green” energy projects. The carbon tax money is double- and triple-spent.

Do You Want a Carbon Tax That Reduces Emissions or Doesn’t Hurt Growth?

Cass goes on to point out another dimension of the shell game: Proponents can demonstrate a carbon tax’s ability to put a dent in climate change, if they make the carbon tax draconian enough. However, when they want to reassure Americans that the pain won’t be too bad, the proponents show estimates from a much smaller carbon tax.

Cass gives a specific example of this rhetorical trick:

If we grabbed the wrists of carbon-tax advocates and demanded they turn over the shells all at once, we would find there was never a marble to begin with. Implementing a US Carbon Tax, a book released on Earth Day [2015] by the American Enterprise Institute, the Brookings Institution, the International Monetary Fund, and Resources for the Future, provides a particularly transparent example. Chapter 4, “Carbon Taxes to Achieve Emissions Targets,” studies carbon taxes that would cut U.S. emissions in half by 2050 and finds an average price of $35 per ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) in 2020, rising to $163 in the final year. Chapter 5, “Macroeconomic Effects of Carbon Taxes,” studies the impact of carbon taxes on the economy but reviews taxes with an average starting value below $20 per ton of CO2 and a 2050 value averaging less than $90 per ton. A “carbon tax” helps the environment, and a “carbon tax” has manageable economic effects — but the two are not at all the same tax. [Bold added.]

Let me paraphrase Cass’s remarks to make sure the reader appreciates them. Cass was studying a very scholarly tome put out jointly by several organizations that support a carbon tax.

In order to demonstrate its potency, the book argued that a carbon tax had the power to reduce U.S. emissions in half by the year 2050. But in order to achieve that drastic result, the authors assumed a carbon tax that hit $163 per ton in the year 2050.

In the next chapter of the book, the authors sought to reassure the reader that the “Macroeconomic Effects of Carbon Taxes” wouldn’t be so awful. Yet the figures showing the impacts on the economy assumed a carbon tax that maxed out in 2050 at less than $90 per ton.

As Cass wryly observes, these are not the same carbon tax—it was much more aggressive in Chapter 4 when the authors wanted to showcase its ability to tackle climate change, but it became much weaker in Chapter 5 when the authors wanted to illustrate its benignity.

Conclusion

Oren Cass’s 2015 essay on the typical case for a U.S. carbon tax is a tour de force. In this post I illustrated Cass’s reasons for calling it a “shell game.” Simply put, the carbon tax proponents often make contradictory promises to different groups in order to garner support.

In the next post I’ll look at more technical issues, in which Cass highlights the fallacies that even trained economists commit when they casually tout a carbon tax.