The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is pursuing an aggressive regulatory agenda so sprawling that at least two of its major regulations seem to conflict with one another, undermining the agency’s stated goals. EPA has proposed severe reductions in ground-level ozone levels, but complying with that rule could hamper states’ ability to comply with the EPA’s so-called “Clean Power Plan.”

EPA’s ozone limits would likely restrict natural gas production in key shale gas regions. Yet using more natural gas is a crucial “building block” of the EPA’s CO2 rule—EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy has even called natural gas a “game changer” in this regard. If using more natural gas were off the table due to new ozone limits, many states would likely find it more difficult and expensive to comply with EPA’s CO2 regulation.

The bottom line: EPA’s regulatory agenda contradicts itself while imposing enormous economic costs on Americans, all while air quality continues to improve without further federal intervention. For these reasons, EPA should withdraw its ozone and carbon dioxide rules.

How EPA’s Ozone Rule Conflicts with “Clean Power Plan”

EPA has proposed cutting the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) for ozone from 75 parts per billion (ppb) to between 70 and 65 ppb (the agency will accept comment on as low as 60 ppb). Setting aside the dubious science EPA uses to justify further lowering the ozone standard, if EPA sets the standard at 65 ppb, it would put vast swaths of the country in so-called “nonattainment.” (According to an analysis by NERA Economic Consulting, that could make the rule the single costliest regulation in U.S. history.)

A nonattainment designation forces states to implement various pollution control measures, some of which EPA hasn’t even defined. These controls could impact a variety of manufacturing activities, including natural gas production. According to the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), “New oil and natural gas production could be significantly restricted in parts of the country classified as ‘nonattainment’ areas, limiting supplies of critical energy resources and potentially driving up costs for manufacturers and households.”

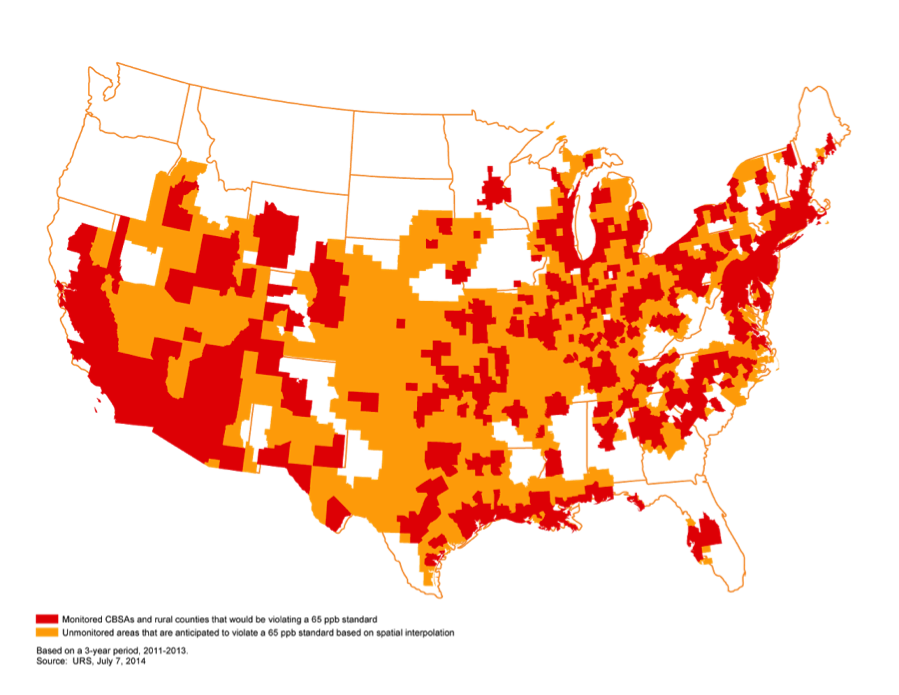

Below is a map of area NAM predicts would be deemed in nonattainment under a 65 ppb ozone standard.

Areas Expected to Violate 65 ppb Ozone Standard

Source: National Association of Manufacturers and American Petroleum Institute

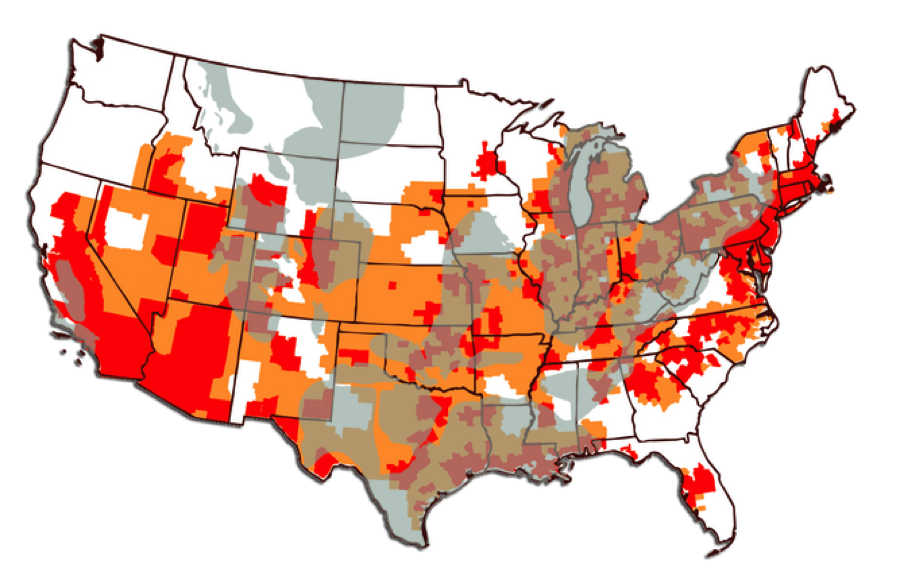

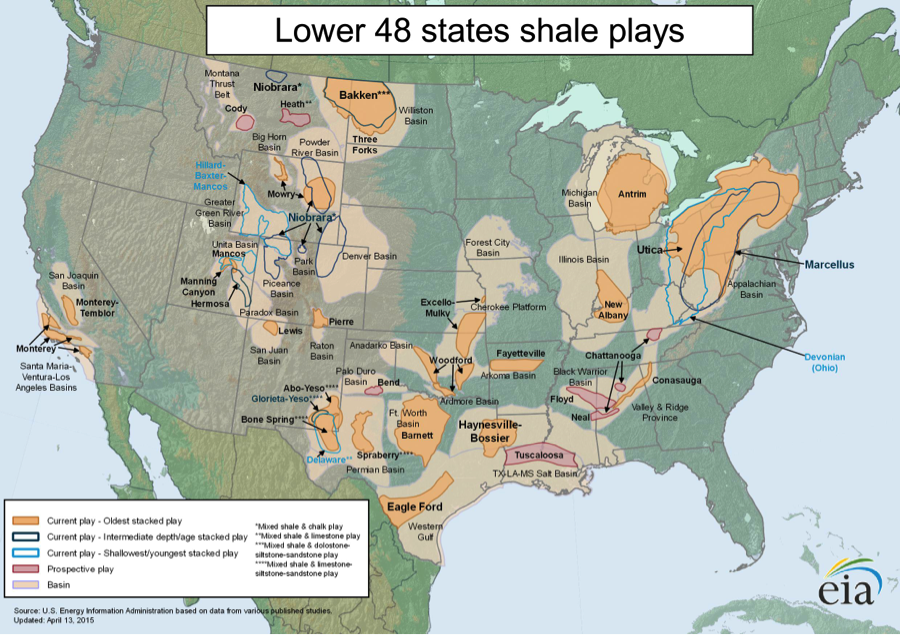

If the above map is accurate, areas with some of the largest shale gas plays in the country could be deemed in non-attainment under EPA’s ozone rule. These shale formations represent half of all U.S. natural gas production and are responsible for almost all of recent production growth that is powering America’s domestic energy boom. In the below map from the American Chemistry Council, note the overlap between potential nonattainment areas and U.S. shale plays:

U.S. Natural Gas Areas Threatened by 65 ppb Ozone Standard

Source: American Chemistry Council

As the map shows, large swaths of almost every shale gas formation, including six out of the top seven plays, could fall into nonattainment under EPA’s proposed ozone rule. Those six shale formations—the Marcellus, Eagle Ford, Haynesville, Permian Basin, Niobrara, and Utica—accounted for close to 100 percent of domestic natural gas production growth over the last three years.

Source: Energy Information Administration

If EPA’s ozone rule curtails natural gas production in these key shale areas, it could complicate compliance with EPA’s so-called “Clean Power Plan.” EPA has proposed cutting carbon dioxide levels by 30 percent by 2030. One of the four “building blocks” on which EPA’s CO2 rule rests is shuttering coal-fired power plants and replacing them with gas-fired plants. This fuel switching, and being able to do it without dramatically higher electricity and natural gas prices, depends on our ability to continue producing large amounts of natural gas from shale formations—many of which are threatened with “nonattainment” under EPA’s ozone rule.

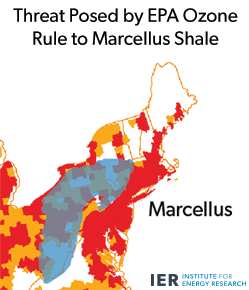

Notably, threatened areas include nearly all of the Marcellus shale, which produces twice as much natural gas as the next two largest formations combined. The below map shows the overlap between Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale and expected ozone nonattainment areas:

The same is true for the other shale plays above, including Colorado’s Niobrara, Texas’ Permian Basin and Eagle Ford, Louisiana’s Haynesville, and Ohio’s Utica. Most of Colorado’s natural gas output, for instance, is concentrated in the northern Front Range, much of which NAM expects to receive a nonattainment designation under a 65 ppb ozone standard. That could jeopardize Colorado’s thriving energy industry, whose dramatic growth has made the state the sixth largest natural gas producer.

It’s worth noting that EPA is also clamping down on methane emissions, which could also curtail natural gas production.

Natural Gas Key ‘Building Block’ of EPA’s CO2 Rule

Increasing natural gas use is critical to EPA’s costly CO2 rule. But if EPA’s ozone rule constrains natural gas production, it could limit states’ options for complying with EPA’s CO2 rule—despite EPA claiming its CO2 rule offers states “flexibility” to choose how to comply. Even Gina McCarthy admits that natural gas is crucial to EPA’s CO2 agenda: “natural gas has been a game changer with our ability to really move forward with pollution reductions that have been very hard to get our arms around for many decades.”

If less affordable natural gas is available, compliance costs for EPA’s CO2 rule would likely skyrocket. EPA talks about using renewables like wind and solar, but these sources are not substitutes for natural gas because wind and solar cannot be counted upon to produce electricity when it is needed. The other building blocks—heat-rate improvements at coal plants and energy efficiency mandates—can only go so far. Without natural gas as a “game changer,” states’ options for compliance will be significantly more limited and costly.

Conclusion

EPA’s regulatory agenda has become so expansive that the agency’s own rules conflict with one another. EPA’s ozone rule undermines the foundation of EPA’s CO2 rule. While EPA’s CO2 rule drives the use of more natural gas at the expense of coal, the agency’s ozone rule could restrict natural gas output in key shale formations right when states need more natural gas to comply with the CO2 rule. EPA could simply exempt shale-producing regions from its ozone rule, but that fails to address the more fundamental problem: EPA’s out-of-control agenda.

EPA’s regulations impose huge costs for small benefits. The agency’s ozone rule could be the single costliest regulation in U.S. history, even though ozone emissions have declined 33 percent since 1980. Meanwhile, EPA’s CO2 rule will impose double-digit electricity rate hikes for residents of 43 states, but limit global warming by just 0.02 degrees Celsius. The solution is for EPA to withdraw its proposed ozone and CO2 rules.