ThinkProgress recently published a post that begins with a provocative quote from Edward Abbey, “Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell.” The post argues that some economic growth is acceptable while other economic growth is bad and does not explain the distinction. The obvious problem is that economic growth and the attendant growth in natural gas, oil, and coal use have led to dramatic improvements in human welfare around the world over the last few decades.

According to data from the World Bank, in countries around the world, consuming more energy and generating more electricity have been correlated with living longer, reducing child mortality, improving sanitation facilities, increasing levels of economic growth, and decreasing air pollution. Furthermore, it is hard to argue there is much “growth for growth’s sake” occurring when 1.3 billion people still do not have access to electricity and 2.6 billion people are without clean cooking facilities.

Economic Development is Vital for Human Development

Economic development is a critical component of improving human well-being, and energy use is indispensable. The International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook, explains:

“Energy alone is not sufficient for creating the conditions for economic growth, but it is certainly necessary. It is impossible to operate a factory, run a shop, grow crops or deliver goods to consumers without using some form of energy. Access to electricity is particularly crucial to human development as electricity is, in practice, indispensable for certain basic activities, such as lighting, refrigeration and the running of household appliances, and cannot easily be replaced by other forms of energy.”

This means that improving economic and human development almost certainly entails increasing the use of energy around the world. ThinkProgress, on the other hand, argues that we have not seen meaningful growth in recent years:

“We have not been growing in any meaningful sense of the word for a while now — certainly not the kind of growth that matters to our children and grandchildren and countless future generations encompassing billions and billions of people.”

Tell that to China and India’s residents, who have experienced higher standards of living and greater prosperity over the last three decades or so. Today, hundreds of millions of people in those countries are no longer desperately poor because of economic growth and the growth in the use of energy. Both countries have seen higher life expectancies at birth, more widespread access to improved sanitation facilities, and a lower child mortality rate. Energy growth has fueled these improvements.

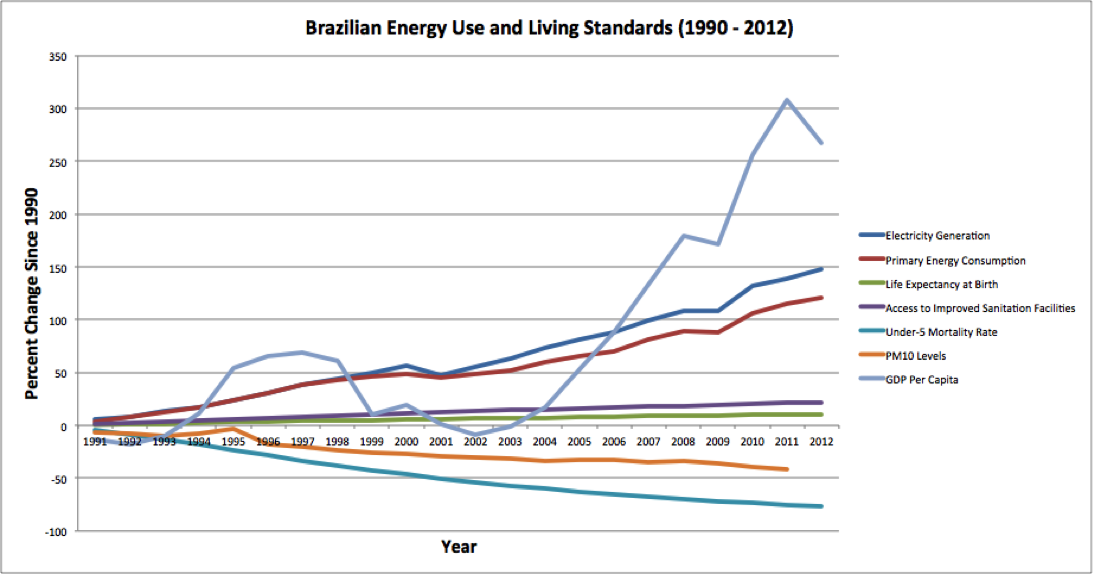

It is not just China and India, though—a similar story is true in both Brazil and the U.S. The following chart, using data from the World Bank and BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy 2014, illustrates the relationship between higher energy use and greater standards of life (including declining PM10 air pollution):

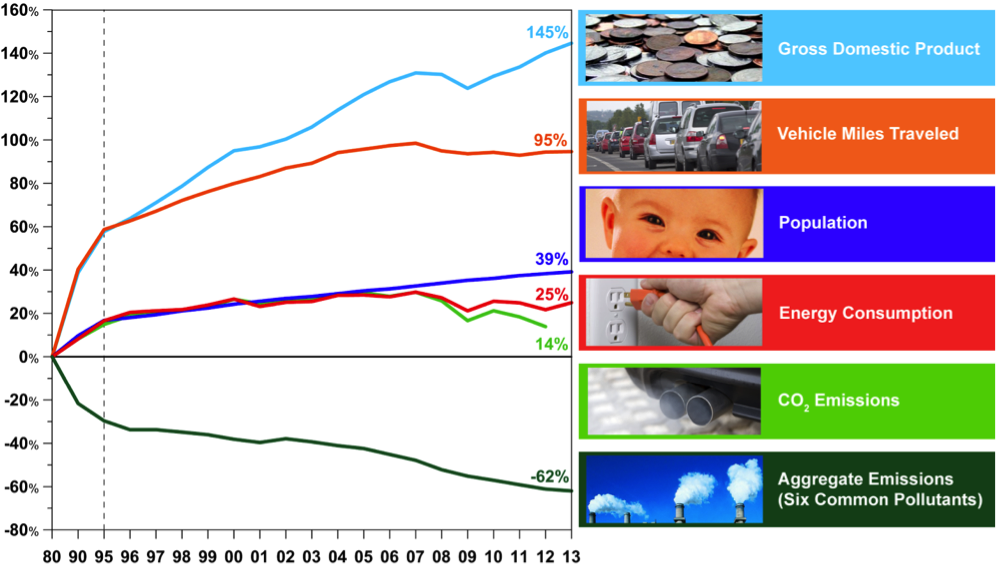

In the U.S., the Environmental Protection Agency also illustrates the relationship between higher energy use and prosperity. The following chart reveals that, as energy consumption and vehicle miles traveled have increased, so has economic growth, while air pollution has dropped off over time:

The use of energy is ultimately vital to living standards, and it is not simply “for the sake of growth.” India, China, Brazil, and the United States have seen not only dramatic increases in energy growth, but also improvements in human welfare. This energy growth surely does not seem like “growth for growth sake.”

Basic activities such as refrigerating food and medicines as well as air-conditioning schools and hospitals are impossible without affordable, reliable energy. Life-saving technologies, too, such as incubators for children born prematurely, also cannot exist without reliable electricity. Because more than 1 billion people do not have access to electricity, the world’s energy use will continue to grow as more people gain access to these improvements.

But aren’t we running out of natural gas and oil?

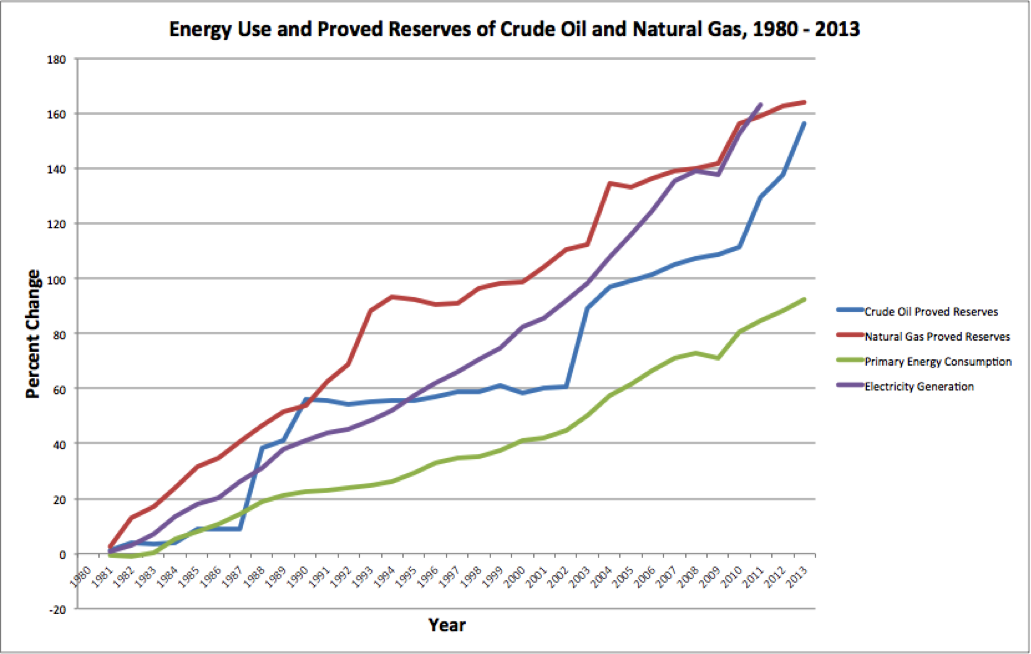

With the increase in energy use, some people may worry that we might be running out of natural gas and oil. It turns out, however, that over the last 30 years, proven reserves of natural gas and oil have kept pace with the increase in electricity generation and have increased much more than primary energy consumption. [1]

The fact that proven energy reserves have increased should not come as a surprise if you consider what the greatest natural resources are—human imagination and intellect, as Julian Simon explained in his book, The Ultimate Resource. As the demand for resources grows, people look for new ways to develop resources and for substitutes for those resources. This desire to satisfy demand leads to innovations in finding and developing energy. The revolutions in shale oil and gas and hydraulic fracturing illustrate this reality. As the demand for energy grew, developers came up with new techniques to find resources that were previously not recoverable.

Conclusions

Saying there is “growth for the sake of growth” is a nice sound bite, but it difficult to see in a world where billions of people do not have access to electricity and clean cooking facilities. History over the last few decades shows us that economic growth and the growth in energy use have led to great improvements in human welfare. Today, people use energy to power hospitals with incubators that can save premature children, to communicate over thousands of miles, and to keep food and medicines from spoiling with refrigeration. Many people in countries like China and India, who have experienced tremendous growth in energy use over the last three decades or so, would likely disagree with the notion that that growth was just “for the sake of growth.” Instead, they would likely point to real, tangible benefits that have materialized in their lives because of affordable, reliable energy.

[1] EIA defines “proved reserves” as “the estimated quantities which geological and engineering data demonstrate with reasonable certainty to be recoverable in future years from known reservoirs under existing economic and operating conditions.” This is a relatively conservative estimate of quantities of resources available.

This graph does not include coal reserves because EIA only lists reserves for the year 2011, and BP’s Statistical Review workbook only lists them for the year 2013.