The Australian government has voted to repeal its carbon tax, becoming the first major power to do so. For those (like us at IER) who believe carbon taxes harm consumers in exchange for no corresponding environmental benefits, the move signals benefit for the Australian people. Yet the episode also carries lessons for the U.S. debate: By showing the fragility of foreign participation in a carbon scheme, the Australians have also repealed the intellectual case for an American carbon tax.

Why the Aussies Hated Their Carbon Tax

As the Wall Street Journal reports:

Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who made a pre-election “pledge in blood” to voters and business to prioritize growth above climate shift, delivered on his promise after independent senators with deciding votes in the upper house sided with his conservatives, following a power shift this month that ended years of domination by the pro-environment Greens party.

“Today the tax that you voted to get rid of is finally gone, a useless destructive tax which damaged jobs, which hurt families’ cost of living and which didn’t actually help the environment is finally gone,” a jubilant Mr. Abbott told voters in a news conference after the Senate’s decision.

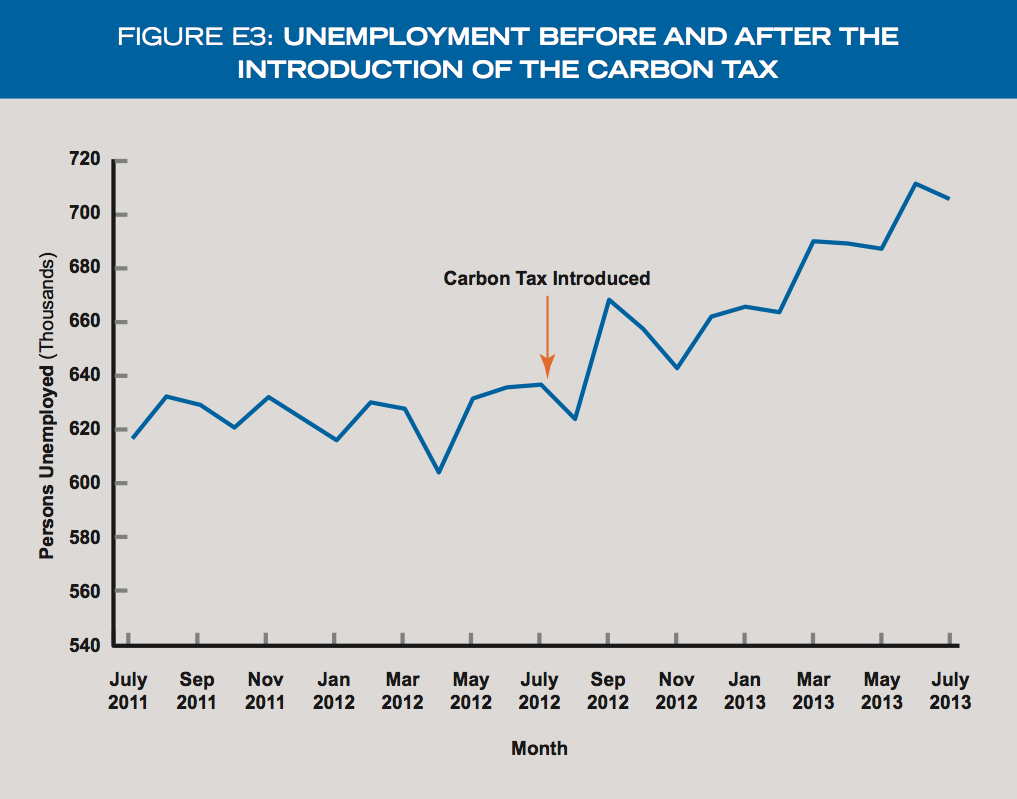

Indeed, in a lengthy study commissioned by IER (which I explain in this post), Australian economist Alex Robson explained last September that the introduction of Australia’s carbon tax went hand-in-hand with spiking electricity prices and a weakening labor market. Here is one key graph from Robson’s report:

Furthermore, beyond the macro statistics, Robson’s study included anecdotal evidence of specific firms that had laid off workers, where the owners themselves cited Australia’s carbon tax as a key factor.

Aussie Episode Repeals CASE for U.S. Carbon Tax

Yet the whole episode has implications on the American debate too. First of all, everyone acknowledges that unilateral U.S. action will do just about nothing. For example, the Obama Administration’s new proposed rules on power plants by themselves will reduce global warming by a whopping—drumroll please—0.02 degrees Celsius by the year 2100.

The progressives who clamor for a carbon tax know this, though they try not to draw attention to such an awkward fact. The response is to claim that the U.S. government must exercise “leadership” on climate change, and that if Americans don’t take bold steps to limit emissions—even though these steps by themselves will do virtually nothing—then we can’t possibly expect China or India to follow suit.

In this context, we can see the significance of the Australian repeal. If even a thoroughly developed country like Australia abandons its carbon tax soon after its introduction because of economic difficulties, then how can we possibly expect the people in China or India to consign themselves to slower economic growth, for decades on end, in order to placate Western environmentalists?

Finally, the Australian case also puts the nail in the coffin of a typical “conservative” argument for a carbon tax, which claims that it will provide “policy certainty” to businesses so that they can invest in “green technology” with confidence. No, a U.S. carbon tax would do no such thing. Even if a carbon tax were implemented, business owners would still have to wonder whether future voters would come to their senses and repeal it, as happened in Australia.

Conclusion

Australia’s repeal of its unpopular carbon tax shows that their citizens (by electing Abbott whose position was crystal clear) favor economic growth over symbolic gestures that don’t even achieve environmental objectives. Furthermore, the Australian repeal devastates the case for a U.S. carbon tax. Nobody can realistically argue at this point that foreign governments will faithfully implement strong limits on emissions, and the claim that a carbon tax would provide “policy certainty” also goes out the window. Let’s hope the “scientific empiricists” who favor a carbon tax adjust their views in light of this new evidence.