In the latest Economic Report of the President, the Obama Administration devotes an entire chapter to its policies on climate change. As usual with such matters, the narrative begins with defensible statements about natural science, and then leaps to completely unwarranted policy recommendations without even attempting to give a cost-benefit justification. In the present post I’ll walk through some of the most serious half-truths and omissions to show just how weak the Administration’s position on carbon policy really is.

Clarifying the Nature of the Climate Change “Threat”

The chapter opens with the familiar focus on the natural science aspect of the debate:

The most significant long-term pollution challenge facing America and the world is the anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases. The scientific consensus, as reflected in the 2009 assessment by the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP) on behalf of the National Science and Technology Council, is that anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases are causing changes in the climate that include rising average national and global temperatures, warming oceans, rising average sea levels, more extreme heat waves and storms, and extinctions of species and loss of biodiversity. A multitude of other impacts have been observed in every region of the country and virtually all economic sectors.

The irony here is, one could accept the above statements at face value, and yet it still wouldn’t follow that the U.S. government’s policies regarding climate change are economically beneficial. It has been very convenient for proponents of massive government intervention in the energy sector to frame the debate as hard-working climate scientists versus the ignorant hordes of “deniers,” but in truth the economic component to the Administration’s policies presents the gaping hole in their arguments.

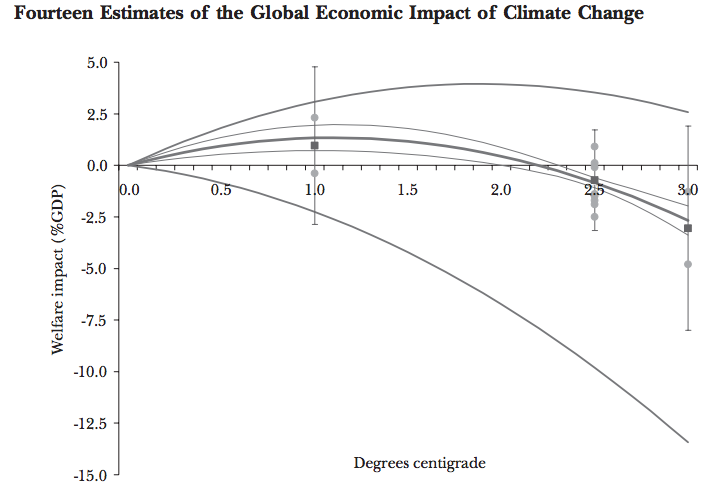

To give just one example of how much the public has been misled—including by the paragraph quoted above—consider the following chart of the projected economic impacts of unrestricted carbon emissions, which comes from Richard Tol’s 2009 Journal of Economic Perspectives paper. In this survey article, Tol looks at more than a dozen studies (published from 1994 through 2006) that used different methods and assumptions to estimate the impact of climate change on human welfare. Tol summarizes the results of his survey in the following figure:

As Tol’s diagram quite clearly indicates, the consensus of economic studies finds that at least the first 2C degrees of global warming would be on net beneficial to human welfare, and this is relative to the current baseline, not to preindustrial times. According to the latest IPCC projections (I show the diagram in this earlier blog post), this amount of additional warming will probably not occur—even with “business as usual” carbon emissions—until the year 2060 or even later. In other words, the peer-reviewed, “consensus” economics literature, in conjunction with the peer-reviewed “consensus” models of global temperature, suggest that unrestricted carbon emissions will provide net benefits to humanity for the next fifty years. This is so completely at odds with what Americans hear every day in the media, that I encourage readers to follow the links if they don’t believe me.

Now I don’t want to commit the opposite sin and mislead IER readers in the other direction: Richard Tol and many of the other economists involved in the studies summarized above, may in fact support a (modest) carbon tax right now. This is because they view the global temperature as akin to a cruise liner that can’t turn on a dime. Nonetheless, I think it is crucial for citizens to realize that all of the measures which will undeniably cause economic hardship and higher energy prices in the present, are based on projections of what bad things will otherwise happen starting in the year 2060. Anyone with an ounce of humility will see that that is a far different proposition from what the Administration’s rhetoric suggests.

More Half-Truths on “Social Cost of Carbon”

The Administration document soon segways into the textbook economic argument for dealing with pollution and other forms of “market failure”:

From an economist’s perspective, greenhouse gas emissions impose costs on others who are not involved in the transaction resulting in the emissions; that is, greenhouse gas emissions generate a negative externality. Appropriate policies to address this negative externality would internalize the externality, so that the price of emissions reflects their true cost, or would seek technological solutions that would similarly reduce the externality. Such policies encourage energy efficiency and clean energy production.

Later on, we see estimates of the size of this “negative externality”:

In 2010, a Federal interagency working group…produced a white paper that outlined a methodology for estimating the SCC [social cost of carbon] and provided numeric estimates (White House 2010). The SCC calculation estimates the cost of a small, or marginal, increase in global emissions. This process was the first Federal Government effort to consistently calculate the social benefits of reducing CO2 emissions for use in policy assessment…

To estimate the SCC, the working group used three different peer-reviewed models from the academic literature of the economic costs of climate change and tackled some key issues in computing those costs. One issue is the choice of the discount rate used to compute the present value of future costs: because many of the costs occur in the distant future, the SCC is sensitive to the weight placed on the welfare of future generations…

The working group report provided four values for the social cost of emitting a ton of CO2 in 2011: $5, $22, $36, and $67, in 2007 dollars. The first three estimates, which average the cost of carbon across various models and scenarios, differ depending on the rate at which future costs and benefits are discounted (5, 3, and 2.5 percent, respectively). The fourth value, $67, comes from focusing on the worst 5 percent of modeled outcomes, discounted at 3 percent. All four values rise over time because the marginal damages increase as atmospheric CO2 concentrations rise. [Bold added.]

In the first place, it is rather dubious to present an estimate of the “social cost of carbon” that ranges from $5 to $67, a range that varies by a factor of thirteen. Furthermore, the reasons for the wide range are also disconcerting: The higher values are generated by picking very low “discount rates” and/or by focusing on “the worst 5 percent of modeled outcomes.” If we pick a reasonable discount rate of 5 percent, and take the average of all modeled outcomes (rather than focusing just on the “worst 5 percent” of possible outcomes), then the Administration’s own working group computed a social cost of carbon (in 2011) of a mere $5 per ton. This is hardly consistent with the claims of the urgency for immediate action.

Even here, it’s not simply that the Administration’s analysis has to rely on low discount rates and worst-case-scenario thinking: they are ignoring a huge factor in the peer-reviewed economics literature. Namely, they are ignoring the “tax interaction effect,” which shows how a naïve setting of tax rates based on the “social cost of carbon” can lead to large economic losses. The problem is that the U.S. already has an inefficient tax code, and so adding a carbon tax on top of it will exacerbate the inefficiency, even if the carbon tax made sense from a textbook “negative externality” approach.

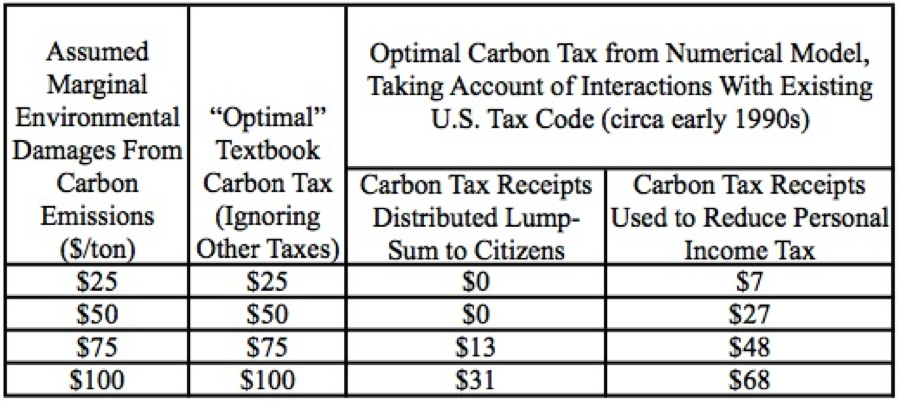

I spell out the full details in this article, but for our purposes consider this table based on the work of pioneers in this area of research:

What the table above shows is that even with a “social cost of carbon” of, say, $50/ton, the optimal carbon tax would be zero if the revenues were distributed back to citizens in a way that didn’t reduce their other tax burdens. Even if the carbon tax were used to reduce the personal income tax dollar-for-dollar (which will never happen in the actual political realities of such a tax), the optimal tax would only be $27/ton, which cuts the textbook remedy almost in half.

Thus we see that even using the cutting edge, peer-reviewed research, the Administration’s arguments for imposing a carbon tax calibrated to the “social cost of carbon” do not work.

Conclusion

There are problems with the conventional case for a carbon tax; I outline some of them in this academic article. But my point in the present post was to show that the Administration’s claims regarding climate change and carbon policy are based on half-truths and omissions, even if we take the economics literature at face value. According to the best estimates, human-caused global warming will provide net benefits to humanity for the next 50 years. Furthermore, the Administration’s own estimates of the harms of carbon emissions range all over the map, showing just how malleable such “computations” are. Finally, the best research on the economics of climate policy shows that even a large “social cost of carbon” should not necessarily lead to a corresponding carbon tax, because of prior inefficiencies in the U.S. tax code.