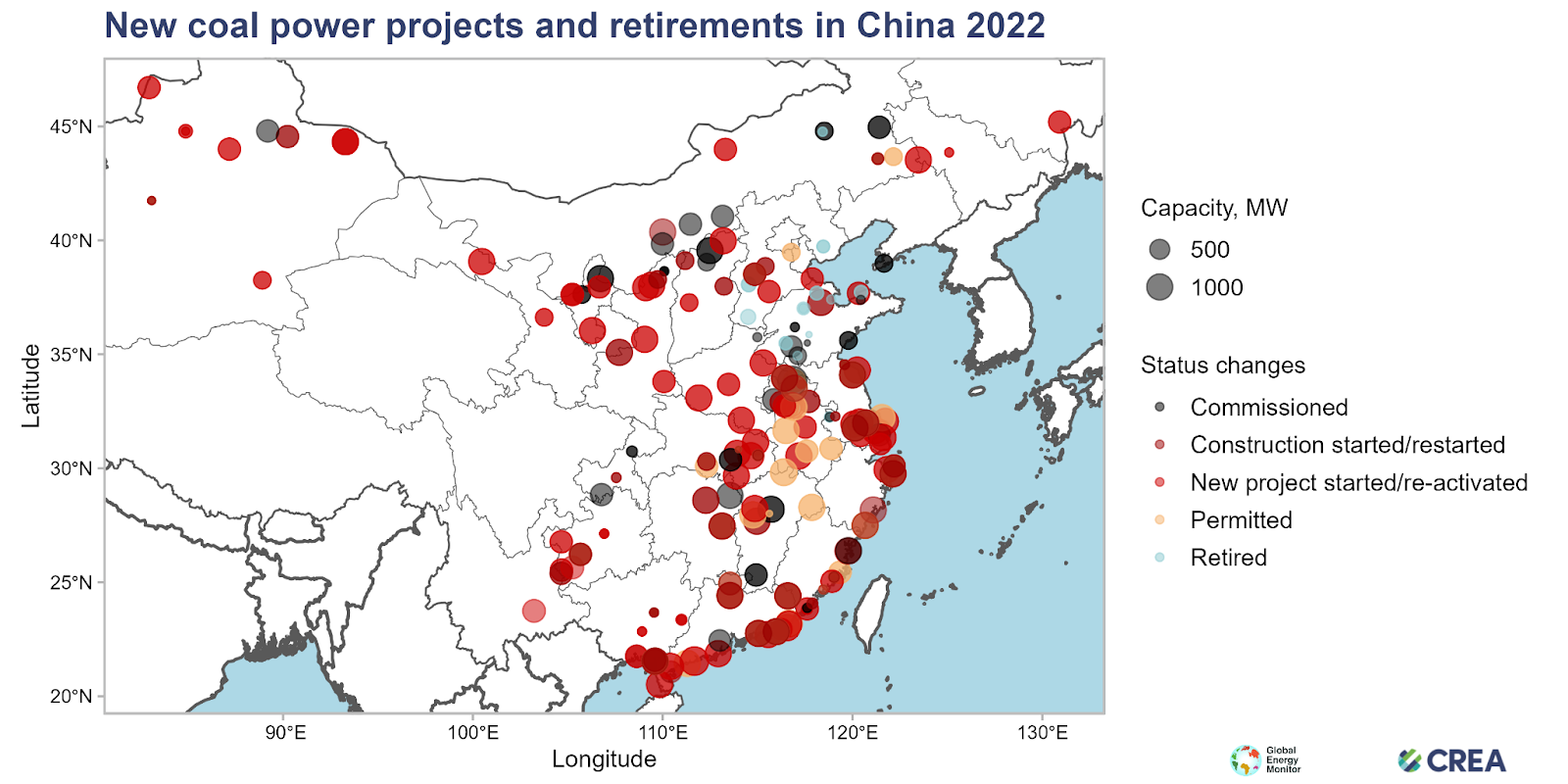

Local governments in China last year permitted 106 gigawatts of coal-fired capacity, about four times more than in 2021 and the equivalent of two large coal power plants per week–a total of 168 coal-fired units spread across 82 sites. It was also the highest amount permitted since 2015, according to a report by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Global Energy Monitor (GEM). Construction began on 50 gigawatts of those coal plants in 2022, a more than 50 percent increase from 2021. Several projects were able to obtain permits and financing and start construction within months of being announced. For comparison, all the generating stations in the UK from all sources combined add up to less than the 106 gigawatts that China permitted in 2022 of just coal units. China is expected to add 70 gigawatts of coal- and natural gas-fired generation in 2023. It is building coal plants to make its power system more reliable as the world pushes to electrify everything from heating to transportation, which will put more strain on the electric grid. China also needs affordable and reliable energy to run its industrial facilities, as it is the largest manufacturer in the world.

China’s new coal capacity connected to the grid had slowed in recent years after a decline in new approvals over the 2017-2020 period, but it is expected to rebound over the next few years, due to concerns about power shortages. Last summer’s drought and heat wave dried up generation from the country’s hydroelectric dams and increased electricity demand for air conditioners, which are becoming more common in China as the country increases its prosperity. Peak demand increased by more than 20 percent from a previous record. Power was cut to factories in hydroelectric areas such as Sichuan province, and aluminum smelters in Yunnan are still operating at reduced rates months later. China saw a rapid increase in peak loads in 2021 to 2022, with the highest recorded peak load increasing by 230 gigawatts. To avoid energy shortages, government officials have indicated that coal-fired generation is critical for the country’s economy. Many of the newly approved projects are identified as “supporting” baseload capacity designed to ensure the stability of the power grid and minimize blackout risks.

China has closed some small and efficient coal-fired units, but the number of closures is small. It closed 4.1 gigawatts of capacity last year and 5.2 gigawatts in 2021 in a coal fleet of well over 1000 gigawatts. Policies on closing down small and inefficient plants have been revised to keep these plants online instead as back-up or in normal operation after retrofitted units.

China also leads the world in wind turbines and solar panels, with installations expected to increase again from a record reached last year. China installed about 125 gigawatts of wind and solar power capacity last year according to government data, though both inherently work at fractions of their nameplate capacity. In 2023, the country is expected to bring 100 gigawatts of new solar power capacity and 65 gigawatts of wind power online. China is also the global leader in hydroelectricity production.

China’s electricity demand is expected to increase by about 6 percent this year, compared to 3.6 percent in 2022. According to government officials, China’s economy post-pandemic is expected to rely on coal-fired power plants, despite the average coal unit operating at only half its capacity. China accounts for about half of the world’s coal production and consumption, gets about 60 percent of its electricity from coal-fired power plants, and relies on coal imports to supplement its domestic production. China’s imports of coal from Russia were up 20 percent in 2022, to 68.06 metric tons. China imported additional Russian coal as other countries turned away from Russian exports due to the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Western sanctions, which drove down its price.

In 2020, China’s President Xi Jinping said his country’s goal would be for its carbon emissions to reach their highest point before 2030, with the country reaching carbon neutrality by 2060. The country’s new coal-fired generating capacity, however, represents about six times the amount of total coal-fired capacity added over the past year in the rest of the world. According to President Xi, China will “phase down” its consumption of coal after 2026, but there has been no commitment to cease construction of new coal-fired power units. However, China has said it will no longer build coal-fired power plants in other countries.

Of China’s six regional grids, the South and East grid are the only ones that do not have a thermal power overcapacity problem. Yet, 50 percent of newly announced projects and 40 percent of construction starts took place in the grids with overcapacity. Rather than building coal plants, critics want China to scale up investments in renewable generation to cover all of power demand growth and invest in grid expansions to connect areas with too many plants to the regions that legitimately need new capacity, like Sichuan and Yunnan. China has shown repeatedly, however, that it will do what it wants.

Conclusion

China is using its domestic resources of coal and building coal plants to ensure energy security as heat waves and droughts have caused electricity shortages. Along with building coal plants, China is also building solar and wind units, but it wants more baseload capacity from coal and natural gas to ensure the stability of its power grid and to minimize blackout risks. Many are viewing China’s building spree as wasteful given the climate goals that President Xi has established. But these goals will not necessarily be met, particularly if they involve the huge leaps of faith and capability as some of those that President Biden has announced that are now being tested in the real world.