Offshore wind was a very expensive technology even before the supply chain issues from the COVID pandemic started and inflation increased its cost even more. These wind farms are very capital and labor intensive and rising interest rates make them even more so. Despite the cost and already increasing electric bills for American consumers, President Biden wants 30 gigawatts of offshore wind off the Atlantic coast by 2030. That may not happen as New Jersey utility Public Service Enterprise Group Inc. recently said it is deciding whether to pull out of Ocean Wind 1, a proposed project off New Jersey’s coast with a capacity of 1.1 gigawatts. Less than two weeks earlier, New England utility Avangrid Inc. (a part of the Spanish Iberdrola Group) said its similarly sized Commonwealth Wind project was no longer viable due to higher costs and supply chain issues. Avangrid would push back the start dates of both the Commonwealth and another wind project, Park City, by a year due to headwinds including inflation and higher interest rates, supply chain shortages, resource problems and rising prices of raw materials.

Not only is the Atlantic coast slated as a haven for offshore wind in the President’s mind, but California Governor Newsom sees 2 to 5 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity by 2030 and 25 gigawatts by 2045, which will be part of Newsom’s plan to achieve 90 percent renewable energy by 2035. Despite the cost and California’s already skyrocketing electricity prices, the Biden Administration announced the first offshore wind lease sale off the central and northern coasts of California set for December 6, 2022. The lease sale is also the first U.S. sale that could support commercial-scale floating wind development. But, developing utility scale floating wind energy off the California coast is projected to be eight to ten years away. The five California lease areas to be offered by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management have a capacity potential of more than 4.5 gigawatts. The lease sale announcement follows California’s agreement with the federal government in May 2021 to open up the West Coast for offshore wind development.

Some Offshore Wind Projects Are Continuing—for Now

Vineyard Wind, a 62-turbine project planned in federal waters 12 miles south of Martha’s Vineyard, and six projects along the East Coast by Danish developer Orsted are still in play. Cable work began in Barnstable, Massachusetts, last year to connect Vineyard Wind to the New England grid and, after pausing construction to accommodate the summer tourist season on Cape Cod, it is to continue construction again this fall, including underwater work in the ocean. The Prysmian Group, a cable-maker, finished manufacturing two high-voltage export cables at factories in Europe for Vineyard Wind. One is being shipped mounted on a barge positioned atop a semi-submersible vessel to accelerate the trip across the ocean. Vineyard Wind workers surveyed the cable area for potential obstacles, ranging from old lobster traps to unexploded bombs from World War II. A remote-controlled submersible was used to clear the path of a WWII bomb. The project also needs a certificate from federal regulators to begin laying the cable and a legal challenge to its environmental permit from a group of landowners and fishermen is expected, but Vineyard sees current federal permitting rules in its favor, especially since Biden has placed a priority upon the U.S. following Europe into offshore wind.

However, Vineyard now says it may not be viable without changes to a power contract with the state because of escalating global energy costs and supply chain issues. The power purchase agreement filed earlier this year locks in how much Massachusetts’ utilities will pay the wind developer for the electricity it generates, which is needed for securing financing for the wind farm. In a filing with the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities on October 21, the company asked for a one-month freeze on the state’s review of its previously filed power purchase agreement, citing ‘unprecedented commodity price increases, interest rate hikes, and supply shortages as factors affecting whether the wind farm remains economic and whether it can be financed under current terms.’ The warning was also noted by Mayflower Wind, the developer of another state offshore wind project. Massachusetts chose the 1,200-megawatt Commonwealth wind project and the 400-megawatt Mayflower project last year in the state’s third round of wind solicitations. Contracts (power purchase agreements) were filed with the state regulators in May. The Mayflower contract was for $77 per megawatt-hour, and the Commonwealth contract was for $72 per megawatt hour.

In Wainscott, New York, a joint venture of Orsted and Eversource Energy completed much of the onshore work needed to for a 12-turbine South Fork Wind Farm, which will be built 35 miles east of Montauk. The company is to begin drilling a tunnel for its high voltage cable under a local beach in October.

Most of the components being used for Vineyard and South Fork are being manufactured abroad. Prysmian’s two cable lengths were made at factories in Finland and Italy. Vineyard’s foundations (monopoles) are under construction in Germany, and its transition pieces, which connect turbine towers to their foundations, are being built in Spain.

Europe’s Wind Development Status

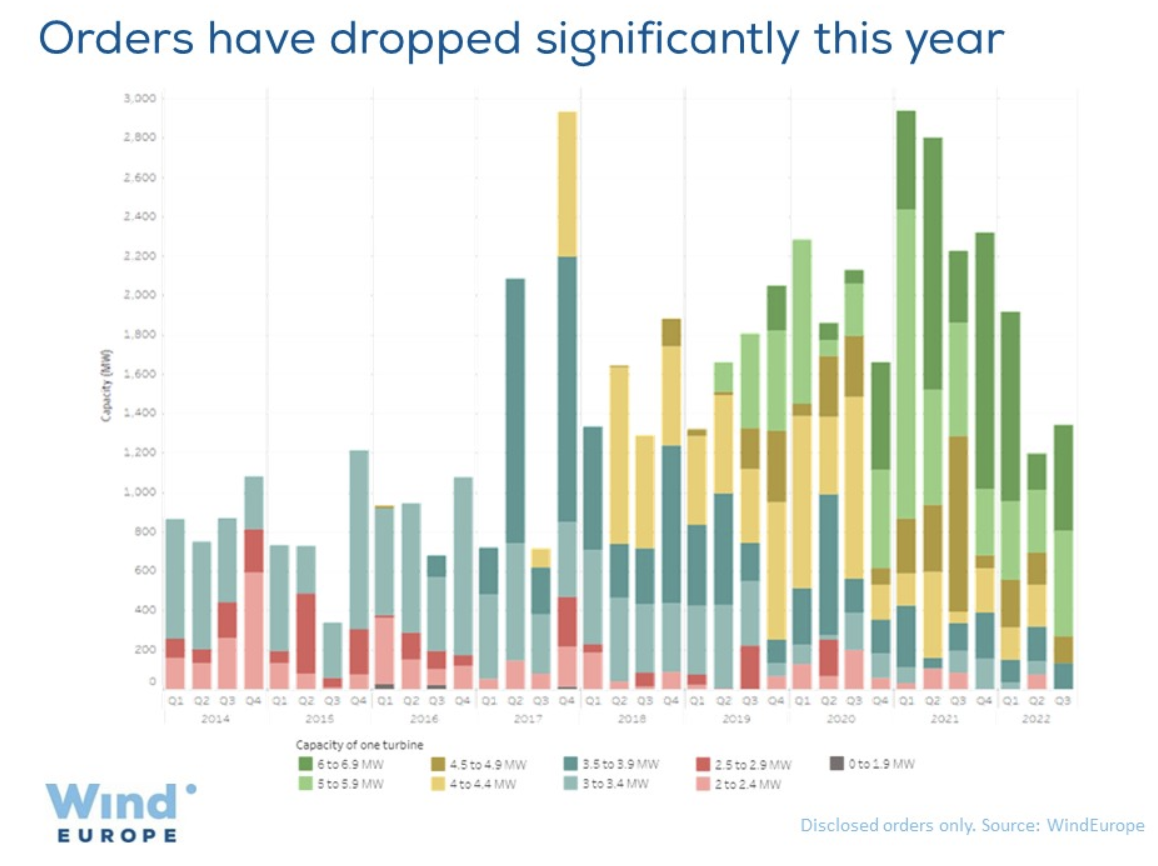

While offshore wind had originally flourished in Europe, inflation, slow permitting and uncertainty around the European Union’s emergency electricity market interventions are currently delaying or stalling orders for new wind turbines. Orders for new wind turbines in quarter 3 of 2022 totaled 2 gigawatts, according to WindEurope. These orders, from 9 countries, were all for onshore wind turbines. Finland ordered the new capacity of 322 megawatts, followed by the Sweden and Germany, bringing total orders in 2022 to 7.7 gigawatts – far below what Europe needs to reach its climate targets. The European Union wants 510 gigawatts of wind energy by 2030, which means the European wind industry needs to install 39 gigawatts of new wind turbines each year up to 2030. The current rate of turbine orders is less than one-fifth of that and falls well short of the target.

Conclusion

Wind Farms are in financial trouble, particularly offshore wind farms that are very expensive and are suffering from rising interest rates, inflation and supply chain bottlenecks. Vineyard Wind off Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts wants its power contract (power purchase agreement) with the state renegotiated, New Jersey’s Ocean Wind 1 is considering whether to proceed at all, as is the Commonwealth Wind project, which is also in need of a power contract renegotiation with Massachusetts. Despite the cost increases and the anxiety of the developers, President Biden’s goal is 30 gigawatts of offshore wind by 2030 and Governor Newsom wants 25 gigawatts by 2045 offshore California. For American consumers, it would be best to follow in Europe’s current footsteps of no offshore wind turbine orders and a significant slow-down in onshore wind turbine orders, as their intermittency means expensive back-up power is needed, which is not included in the cost estimates.