As if our current ethanol requirements are not enough, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has upped the amount of ethanol that can be blended into gasoline from 10 percent to 15 percent for vehicles of model year 2001 and newer. Some American consumers are astute enough to recognize that their mileage per gallon of gasoline declined with the 10 percent blend currently in use, thereby increasing the frequency of fill-ups. Now that trend will be increased if EPA has its way. Ethanol is 34 percent less efficient than gasoline, does little to decrease our greenhouse gas emissions, is heavily subsidized, and has been accused of increasing food prices both directly and indirectly through livestock feed costs.

The EPA’s decision made in October 2010 to allow a 15 percent blend of ethanol into the gasoline mix for model year 2007 and newer cars seems to be motivated largely by politics since that decision was made before the 2010 election where candidates in Midwestern corn states could tout the decision to voters. A further evidence of the politics involved is witnessed by the House of Representatives voting 286 to 135 to block the EPA from using federal funds to implement the increased ethanol volume in gasoline in the continuing resolution to keep the government funded while the fiscal year 2011 budget is being debated.

Among those opposing the E15 implementation are the

- National Automobile Dealers Association and the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers who fear that E15 will damage older cars whose owners mistakenly use E15, that service repairmen could misdiagnosis engine problems by not realizing that the wrong fuel was used, and that damage could occur to the engine, catalytic converter, vehicle diagnostic tests, and/or the check engine light.

- Engine Products Group who represent carmakers and manufacturers of small engines for boats, snowmobiles, and lawnmowers who fear damage to their products.

- Food industries who fear that increased corn demand will result in higher prices for food and livestock feed.

EPA’s E15 Ruling

In March 2009, Growth Energy, a coalition of U.S. ethanol supporters, and 54 ethanol manufacturers applied for a waiver to increase the allowable amount of ethanol in gasoline from 10 percent ethanol to 15 percent ethanol. In order to protect the emission control systems of vehicles and engines, the Clean Air Act prohibits the use of fuels or fuel additives that are not substantially similar to those used in certifying vehicles and engines to emission standards. The Clean Air Act, however, allows EPA to grant a waiver of this prohibition for a fuel or fuel additive if it can be demonstrated that vehicles and engines using the fuel additive will continue to meet emission standards over the “full useful life” of the vehicle.

To respond to the request from Growth Energy and ethanol manufacturers and the provisions of the Clean Air Act, the EPA partially granted a waiver to allow gasoline to contain 15 percent ethanol (E15) for use in model year 2001 and newer light-duty motor vehicles (e.g. cars, light trucks, sport utility vehicles and vans). First, on October 13, 2010, EPA granted a partial waiver for E15 for use in model year 2007 and newer light-duty vehicles, followed by another partial waiver to allow E15 in vehicles of model year 2001 to 2006 made on January 21, 2011. According to EPA, their decisions were based on tests conducted by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) and other information regarding the potential effect of E15 on vehicle emissions. EPA is now working on regulations that will deal with the conditions of ensuring fuel quality and mitigating misfueling. One way to deal with misfueling is to place labels on the product at the pump to identify it as E15 and to indicate its use for 2001 or newer vehicles. EPA will conduct quarterly reviews to ensure retail stations comply with the labeling requirements at the pumps.

Numerous industries have participated in a legal suit against EPA’s waiver including the Engine Products Group, representing carmakers and manufacturers of smaller engine-powered products, and food industries including the Grocery Manufacturers Association, National Meat Association, National Chicken Council, National Pork Producers Council, Snack Food Association and American Frozen Food Institute. Oil companies and refineries are also parties to the suit. In the lawsuits, the groups claim that the EPA violated the Clean Air Act by approving E15 for use in some vehicles, but not in others.

According to Charles Drevna, President of the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association (NPRA), “This goes beyond the matter of EPA violating federal clean air law by granting partial waivers for E15. EPA’s decision to allow E15 in the marketplace before adequate testing has been conducted disregards the safety of consumers. NPRA’s members are committed to providing safe, reliable fuels to the American people. We stand behind the products our members provide, including the E10 used safely by millions of consumers throughout the country every day.”

Potential Issues Resulting From Increasing Corn-Based Ethanol

Because E15 will require a separate pump and because EPA has not absolved blenders from potential liability from customers, blenders are reluctant to implement it. Automobile manufacturers and blenders both worry about engine damage liability. Some environmental and food-producing groups feel that corn-based ethanol is bad for the environment and raises food prices. The Outdoor Power Equipment Institute and the Specialty Equipment Market Association are worried about E15’s impact on older cars and small engines. EPA did not approve the use of E15 for use in smaller engines, like the ones used in boats, snowmobiles and lawnmowers, and in vehicles of model year 2001 and older.

Burning ethanol can cause toxic air pollutants to be emitted from vehicle tailpipes, especially at higher blend levels such as E15. Because ethanol burns hotter than gasoline, catalytic converters can break down faster. Newer vehicles have oxygen sensors which allow them to adjust combustion and protect the catalysts, but older vehicles may have problems. Fueling older cars with the new blend could result in serious damage to the engines, potentially voiding warranties and raising the number of consumer lawsuits. Corn ethanol advocates have been pushing for a liability waiver for oil companies and retailers that would protect them from lawsuits arising from drivers filling their tanks with the wrong fuel.

The food industry is having problems with the increase in ethanol blend mainly due to price increases. When USDA estimated that 2010 corn production would be 3.4 percent less than in 2009, corn prices went up, putting pressure on the meat and poultry industries and resulting in higher food prices for consumers. Also, putting more acreage into corn production reduces production of other grains, increasing their prices as well.

According to Joel Brandenberger, President of the National Turkey Federation, “Feed accounts for 70 percent of the total cost of raising a turkey, and corn is the single-largest ingredient in turkey feed. The spike in corn prices caused by the expansion of corn-based ethanol could be crippling at a time when the turkey industry is just starting to recover. This dramatic increase in feed prices has led most turkey processors to cut production. Increasing the ethanol blend to 15 percent would destroy any chance our industry has of recovery in the future.”

The Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS)

In its wisdom, the Congress passed and then-President George W. Bush signed into law the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007. That act, among other things, contains a renewable fuel standard that mandates the production of ethanol to the level of 36 billion gallons by 2022, where 15 billion gallons was to be corn-based and the remainder was to come from advanced forms of biofuels, namely cellulosic ethanol. The advanced biofuels contribution, starting at 0.6 billion gallons in 2009 increasing to 1.35 billion gallons in 2011 and 21.0 billion gallons in 2022, however, was found to be unattainable. That forced EPA to issue changes to the original act containing four separate standards that include 1.0 billion gallons of biomass-based diesel by 2012 and 16 billion gallons of cellulosic biofuels by 2022, subject to annual assessments that EPA will set each November for the following year.

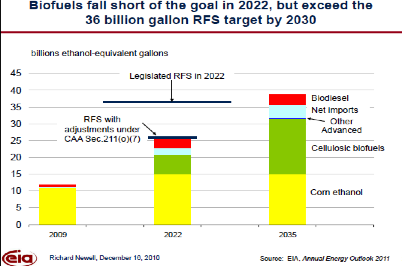

The Energy Information Administration represents the Energy Independence and Security Act in its Annual Energy Outlook forecasts, and has found that the original mandates cannot be reached by the targeted dates. As they note, if biofuel quantities are inadequate to meet the initial targets, the legislation provides waivers and the modification of credit volumes associated with each type of biofuel. That is, more advanced forms of biofuels receive a higher credit value compared to corn-based ethanol.

In 2022, only slightly more than 25 billion gallons of biofuels are forecast to be produced–including corn-based ethanol, cellulosic ethanol, biomass-to-liquids, biodiesel, and imported biofuels– 11 billion gallons below the mandate because economic and technological factors prevent cellulosic biofuel production from providing the credits that would be needed to meet the requirement. As oil prices increase and biofuel production costs decline improving their competitiveness, biofuels production eventually surpasses the mandated level in 2022, as seen by the figure below.

Ethanol Subsidies

Various legislation provided tax subsidies for ethanol production since the Energy Tax Act of 1978. For example, the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 created the Volumetric Ethanol Excise Tax Credit (VEETC) to subsidize the production of ethanol in the United States. VEETC provided a 51-cent per gallon tax credit for ethanol blended into gasoline that was reduced by the 2008 Farm bill to a 45-cent per gallon tax credit. The 2004 bill also provided for a Small Ethanol Producer Tax Credit (SEPTC) of 10 cents per gallon of ethanol produced. The tax credits for blended ethanol with gasoline and for small ethanol producers expired on December 31, 2010.

To encourage domestic production, the American Jobs Creation Act also provided a 54-cent per gallon tariff on ethanol imports that expired at the end of 2010. The Cellulosic Biofuel Producer Tax Credit (CBPTC), which provides producers of cellulosic feedstocks with a $1.01 per gallon credit that includes the VEETC and the SEPTC, was established by the 2008 Farm bill and expires on December 31, 2012. During its lame duck session, Congress passed a one-year extension on the ethanol subsidies that were to expire at the end of 2010 in the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010.

According to the Energy Information Administration, ethanol subsidies in fiscal year 2007 (the last year the study was done) totaled $3.249 billion in 2007 dollars. On a per unit of production basis, the subsidy cost U.S. taxpayers $5.72 per million Btu, more than 190 times the subsidy for petroleum and natural gas on a per unit basis.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the cost to U.S. taxpayers of using a biofuel to reduce gasoline consumption by one gallon is $1.78 for ethanol made from corn and $3.00 for cellulosic ethanol. And, the cost to taxpayers of reducing greenhouse gas emissions through the biofuel tax credits are about $750 per metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent for ethanol and about $275 per metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent for cellulosic ethanol. CBO cautions, “Those estimates do not reflect any emissions of carbon dioxide that occur when the production of biofuels causes forests or grasslands to be converted to farmland for growing the fuels’ feedstocks. If those emissions were taken into account, such changes in land use would raise the cost of reducing emissions and change the relative costs of reducing emissions through the use of different biofuels–in some cases, by a substantial amount.”

It is likely that ethanol would have penetrated the market even without the subsidies and the mandates because it is added to gasoline to help oxygenate the fuel, allowing it to burn more completely, which ostensibly improves emissions. This is particularly true once methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE) was banned by states because of its leakage into ground water. After MTBE, ethanol is the next least expensive oxygenate. However, in the market-based approach, the ethanol volumes would not have reached the levels mandated by the RFS.

The Price of Ethanol

The price of E85, a blend of 85 percent ethanol and 15 percent gasoline used in flex fuel vehicles, on a Btu basis is higher than that of gasoline, which suggests it is inferior in the market compared to gasoline, especially since its price includes subsidies and the RFS mandate. The average national price of E85 is currently $2.98 per gallon, while the national price of gasoline is $3.53 per gallon, resulting in a spread of about 15 percent. While the price of E85 appears to be lower, taking into account that the ethanol component is 34 percent less efficient than gasoline provides an equivalent price of $3.81 per gallon, 8 percent higher than that of gasoline.

Conclusion

The ethanol market is heavily subsidized by a renewable fuel standard and tax credits. Without these incentives, however, the ethanol market would still have penetrated the gasoline blending market because of its properties as an oxygenate fuel, but not to the extent of the RFS mandates. E85 is not price competitive with gasoline on a Btu basis mainly because its ethanol component is 34 percent less efficient than gasoline. Because the gas mileage is poor compared to gasoline and because of the subsidies, the Congressional Budget Office determined that corn-based ethanol has cost consumers an extra $1.78 per gallon of gasoline.

As George Watts, President of the National Chicken Council, said “Rising grain prices driven by the voracious demand for feedstock from the heavily subsidized ethanol industry caused an increase of six percent in the retail price of fresh whole broiler chickens from 2008 to 2010. Channeling even more corn into ethanol will, in time, only drive up the cost of chicken even more. Consumers will end up paying for the ethanol industry’s demands. It is time to put an end to government mandates and interference in the market that raise the price of corn.”