Rising oil prices in recent years have again raised the question whether worldwide oil production has reached a peak. Various analysts have suggested that the rapid run up in prices indicates that if oil hasn’t yet reached its peak of production, it will do so very soon.

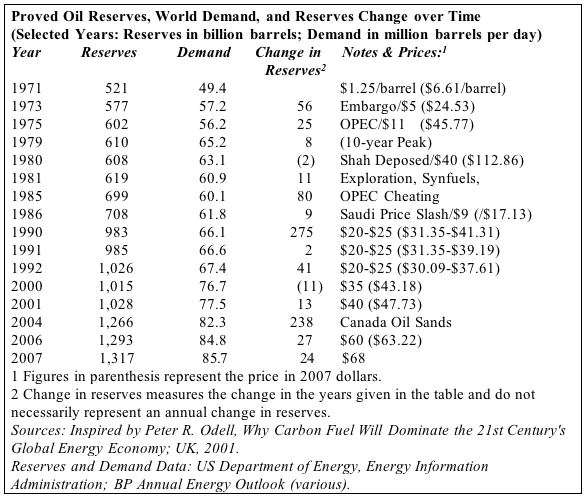

At the same time, though, the world keeps discovering new reserves as higher prices provide incentives to bring more oil onto the market. As the above table demonstrates, the world’s oil reserves have steadily increased in the face of rising consumption.

The Energy Information Administration has reported that “the world production peak for conventionally reservoired crude is unlikely to be ‘right around the corner’ as so many other estimators have been predicting. Our analysis shows that it will be closer to the middle of the 21st century than to its beginning.”

Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA) goes beyond the EIA, suggesting that peak oil production may be more than just a few decades away. Its analysts have written: “Those who believe a peak is imminent tend to consider only proven remaining reserves of conventional oil, which they currently estimate at about 1.2 trillion barrels. In the view of many petroleum geologists, this is a pessimistic estimate because it excludes the enormous contribution likely from probable and possible resources, those yet to be found, and plays down the importance of unconventional reserves in the Canadian oil sands, the Orinoco tar belt, oil shale and gas-to-liquid projects. CERA believes the global inventory is some 4.8 trillion barrels, of which about 1.08 trillion barrels have been produced, leaving 3.72 trillion conventional and unconventional barrels, an order of magnitude that will allow productive capacity to continue to expand well into this century.”

Between 2000 and 2006 in the United States, discoveries of new oil fields have added 2,956 million barrels to U.S. reserves, only 456 million barrels fewer than those from discoveries in the 1980s and 1990s combined. This has occurred despite the fact that areas estimated to hold 32 billion barrels remain off limits because of political (not economic) constraints. The discoveries of new oil fields illustrate how U.S. federal and state policies have affected domestic petroleum supplies in this country. Most of those new oil discoveries have come in the few deepwater tracks where the federal government has allowed exploration. Since 1982, though, Congress has enacted moratoria to prevent offshore oil exploration and development off of most of the continental shelf. It also has restricted development of new oil fields in Alaska and keeps threatening domestic oil companies with higher taxes on their profits and more taxes on any oil they discover and extract.

So why the higher prices? Rapidly increasing demand ahead of new production and development is the primary reason. For instance, in 2007, world liquids demand was 85.7 million barrels per day, while world liquids supply was 84.6 million barrels per day, resulting in a stock drawdown of 1.1 million barrels per day. Supplies will need to exceed demand in the near future to restore petroleum stocks, or prices will remain high.

Why hasn’t production kept pace? As the Aspen Institute has noted, “It’s not a question of what exists below the ground, but the adequacy of the investment environment above ground and the progress made on demand reduction that will lead to wise choices.” This study points out that governments and “government controlled entities” have taken control out of the hands of market forces and consumers, thus reducing the ability of energy markets to meet the needs of consumers.

National oil companies now dominate the world market and control most of the world’s oil reserves. Private multinational oil companies now possess only about 8% of world reserves.

But it isn’t just the major oil producing nations of OPEC and their national oil companies that deter oil production and development. Western governments, including the United States, have pursued policies that have reduced incentives for new oil and gas developments.

There is no technological or natural reason for oil production to peak anytime in the near future. The world has centuries’ worth of ultimately recoverable petroleum reserves, so long as government policies provide a framework conducive to long-run investment in infrastructure and new techniques.