The Trump Administration has enacted tariffs on imported solar cells and larger modules (as well as on washing machines). In general, tariffs are counterproductive, because they only help some producers at the expense of others, and they unambiguously raise prices for consumers. That logic applies to this case as well. However, insofar as the American solar companies that import cells and modules are some of the biggest losers in this deal, they have little grounds for complaint, as they are already receiving lavish benefits from provisions in the tax code. Two wrongs don’t make a right, to be sure, but employment in the renewables sector is arguably closer to the “natural” level after this latest move by the federal government.

The Context for the Announcement

The tariffs on solar cells and modules start at 30 percent in the first year, and then fall by 5 percentage points until reaching 15 percent. According to the Administration, the purpose of the tariffs is to correct for the distortion in trade caused by the Chinese government’s use of “state incentives, subsidies, and tariffs to dominate the global supply chain” in this arena.

Back in the fall, the U.S. International Trade Commission recommended that the federal government enact tariffs in response to China’s allegedly unfair practices. Indeed, the Obama Administration had reached a similar conclusion, as CNBC explains:

The Obama administration twice placed tariffs on solar imports from China, but Chinese companies skirted the penalties by moving production to neighboring countries. The Trump administration’s tariffs close that loophole by applying tariffs to all solar cell and module imports.

I personally don’t recall as much outrage over the Obama Administration’s moves when they occurred.

Tariffs, a Blunt and Inefficient Instrument

In general, economists from across the political spectrum agree that tariffs are a very blunt instrument, and reduce economic efficiency. They, of course, have the ability to help certain producers—that’s why tariffs exist—but in general, the gains to the winners are smaller than the losses to the losers. As such, when the U.S. government imposes a new tariff, it makes Americans per capita poorer than they otherwise would be.

The pithiest case against tariffs was penned by Henry George, who observed: “What protection teaches us, is to do to ourselves in time of peace what enemies seek to do to us in time of war.” (Quote from page 47 here.) For an introduction to the economic case for free trade in modern, plain language, see the chapter in my textbook. For a classic critique of “protectionism,” read the famous satire by the masterful Bastiat.

When it comes to our current situation, the new tariffs will help U.S. manufacturers of solar equipment. Indeed, it was two U.S.-based companies—Suniva and SolarWorld—that brought the case to the government’s attention. By artificially raising the price of imports, the tariffs make it easier for U.S. manufacturers to compete, and thus the move arguably “creates jobs” for such companies. However, these potential job gains are offset by the loss of jobs of U.S. companies that use solar cells and modules, because the higher prices will ultimately mean fewer sales in renewables at the consumer level. These analyses are always guesswork, but according to one estimate quoted by CNBC:

Imposing tariffs could create as many as 6,400 solar manufacturing positions, but job losses in other parts of the industry would almost certainly exceed those gains, an independent analysis by Bloomberg New Energy Finance performed for Utility Dive found.

So to summarize, compared to the situation a month ago, the new tariff on solar cells and modules makes Americans poorer on net. It doesn’t create jobs per se, it just shuffles them around. And by artificially making imports more expensive, it merely reduces options for U.S. consumers.

Remember that a tariff is a tax on potential purchases that Americans want to make. Fans of the free market should not be surprised to learn that the textbook analysis says a tariff (generally speaking) makes Americans poorer, on average, because its artificial incentives make production less efficient. That’s what taxes do.

It’s true that we don’t have a free market in global trade. However, if the Chinese government wants to subsidize its exports of solar products, then that makes the Chinese people poorer. In the limit, if the Chinese government bought up products and then sent them as gifts to Americans, that would be a pure transfer of wealth from China to the United States. Getting gifts from foreigners doesn’t make us poorer, on net, even though the particular type of gift could hurt particular U.S. firms and their workers.

U.S. Renewables Sector Has Little Grounds for Complaint

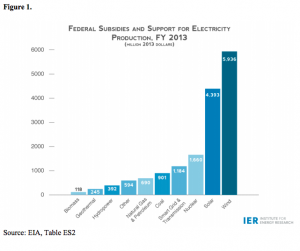

Having said all of the above, the one group who can’t complain about the impact of the new tariffs is the U.S. renewables sector. These firms are already benefiting from artificial tax code support, in the form of the Production Tax Credit (PTC) and Investment Tax Credit (ITC). (Note that the eligibility has changed over the years, but solar operations from the past and not claiming the ITC can still claim the PTC.) Consider Figure 1 below, taken from my March 2017 Congressional testimony on energy subsidies in the tax code:

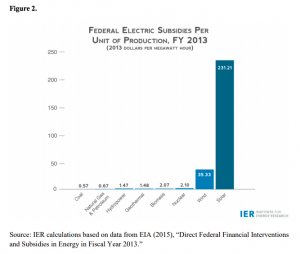

The above chart shows the total dollar amounts (based on government statistics). Things are even more lopsided when we account for the amount of electricity actually produced by the various sources:

As these figures make perfectly clear, U.S. solar producers are the last group in the world who can complain about unfair tax treatment leading to distortions.

Conclusion

As I explained in my testimony last year, the federal tax code artificially boosts the market share of wind and solar power in the United States. Now, the new tariffs enacted by the Trump Administration will reshuffle that artificially high amount, reducing the number of workers in solar installation (for example) while boosting the number of workers in solar manufacturing. Even so, the total number of U.S. workers in “solar” is still artificially high, compared to a situation where the U.S. tax code just applied the same rate to all firms, and didn’t have special credits for some domestic firms, or penalties on foreign imports.

In general, tariffs are a very blunt instrument and a poor device for making Americans more prosperous. However, the U.S. firms who are the direct “losers” of the new solar tariffs have little grounds for complaint, since they’ve been benefiting for years from favorable tax treatment.