Although there is no mention of a carbon tax in the recently released GOP blueprint for tax reform, there had been the familiar chatter of a “grand bargain” wherein Democrats get a carbon tax and Republicans get corporate income tax relief. For example, Edward Kleinbard wrote such an article for the Wall Street Journal earlier in the week.

Because this issue will no doubt continue resurfacing, it’s important to expose the flaws in Kleinbard’s case. He simply ignores the political impossibility of his proposal: why would Democrats agree to a massive new tax falling on poor people, in order to fund tax cuts for corporations? Furthermore, why do we need a “revenue neutral” tax reform plan? As I’ll show, federal spending and taxation are both at relatively high levels, historically speaking. If policymakers want to reduce the deficit, they should trim their budgets, not enact a massive new tax on energy and transportation.

Kleinbard Proposes a False Bargain

Early in his article Kleinbard promises his readers that “there is a powerful bipartisan grand bargain in corporate tax policy waiting to be struck.” Kleinbard goes on to explain:

Republicans are between a rock and a hard place. Growth comes from a permanent low corporate tax rate, not one that expires in 10 years. The GOP should embrace a new revenue-raiser that can attract moderate Democrats without undercutting the economic benefits of reform. The answer? A carbon tax, which raises revenue, satisfies long-term economic efficiency and environmental goals, and is as important to Democrats as corporate tax rate reduction is to Republicans.

Most Republican politicians hate the idea of a carbon tax…And progressive Democrats would never agree to revenue-losing corporate tax reform. Both sides should hold their noses and work toward major corporate tax reform financed in part with a carbon tax. [Kleinbard, emphasis added.]

Look at the way Kleinbard stacks the deck: He simply rules out a net tax cut, by claiming that “progressive Democrats would never agree to revenue-losing corporate tax reform.” Maybe he’s right and maybe he’s wrong, but does Kleinbard really think progressive Democrats would be okay with major corporate tax cuts if it were financed by a big tax hike falling most heavily on poor people?

We don’t need to speculate on this question. We can survey the reaction from progressive Democrats to the current GOP proposal, which involves net tax cuts (and no carbon tax). For example, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) says, “It seems that President Trump and Republicans have designed their plan to be cheered in the country clubs and the corporate boardrooms,” and claimed that Republicans are “going to be in for a rude awakening as the American people are going to rise up against this,” because “It’s little more than an across-the-board tax cut for America’s millionaires and billionaires.”

So does Kleinbard really think the way to get Chuck Schumer on board would be to couple the “across-the-board tax cut for America’s millionaires and billionaires” with a regressive tax that makes electricity, gasoline, and heating oil more expensive?

Can’t Use Carbon Tax Receipts for Multiple Purposes

In the block quotation above, Kleinbard opens up a can of worms when he says that both sides should work for corporate tax reform financed in part by a new carbon tax. As I’ve stressed countless times here at IER, you don’t get a “win-win” by doing a buffet approach. If you levy (say) a trillion dollar carbon tax, and then only devote (say) a third of the money to net corporate tax cuts while allocating the rest of the revenue to provide assistance to low-income households and to fund “green energy” investments, then even on paper you don’t get a boost to conventional economic growth. I’ve already argued that a literal swap—where 100% of all net corporate tax cuts are paid for by a carbon tax—would be worse politically than just the corporate tax cuts.

It’s not clear from his article if Kleinbard means that other, more politically popular tax changes (such as increasing the standard deduction to help regular households) would also be thrown into the “grand bargain” to achieve revenue neutrality, but if so, then he should admit to his readers, “Even if my proposal were carried out perfectly, standard models say it would reduce GDP growth.” If Kleinbard wants to justify such an outcome on environmental grounds, fair enough, but that’s not the impression he left the WSJ readers with his actual article.

Why Insist on Revenue-Neutral Tax Reform?

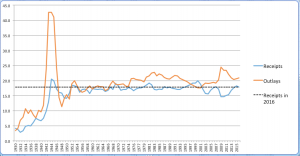

Proponents of a carbon tax act as if any corporate (or other) tax relief must be “paid for” with a levy on greenhouse gas emissions. But why? The following chart—based on OMB historical data—shows that both federal spending and tax receipts are at relatively high levels, historically speaking:

Figure 1. Federal Government Outlays and Receipts, as % of GDP, 1930-2016 (annual)

Source: OMB Historical tables

As Figure 1 indicates, federal government receipts in 2016 stood at 17.8 percent of the entire economy. Look at the dashed black line, where I’ve drawn the current level of the federal tax take back through time. For most of U.S. history, the federal government has taken far less in tax receipts. In other words, for most of U.S. history, the blue line is below the current dashed black line.

Now when it comes to spending, the situation is even clearer: the 2016 level of federal spending—at 20.9 percent of the economy—was much higher than the historical average, at least if we set aside spending during World War II.

To get a more formal result rather than simply eyeballing the chart, consider: From 1950 through 2016, the average figure for federal outlays was 19.5 percent of GDP, compared to the 2016 value of 20.9, meaning we are currently spending 1.4 percentage points more of the economy. On the receipts side, the average from 1950 through 2016 was 17.3 percent of GDP, coming in 0.5 percentage points below the 2016 tax take of 17.8 percent.

In summary, the federal government is currently spending and taxing more than the postwar norm, even when adjusting for the growth in the economy (let alone in terms of dollar amounts). There is no reason to rule out net tax cuts a priori; the U.S. seemed to get along just fine in earlier decades with a smaller tax burden.

If policymakers and pundits are worried about the growing federal debt—as they should be—they should look at spending cuts, not more taxes. Indeed, Kleinbard himself linked to a 2016 CBO study that assessed a carbon tax, but it also listed 54 options for cutting spending.

Conclusion

It is simply not true that a carbon tax is necessary to achieve tax reform. The federal government currently takes in half a percentage point of GDP more in receipts than the postwar average, while spending is 1.4 percentage points higher. If we insist that any tax reform be “deficit-neutral,” then it can be matched with corresponding spending cuts that the CBO has studied, and elsewhere I have itemized more than a trillion dollars in liquid assets that the federal government could privatize.

The fundamental flaw in claims for a “carbon tax swap” involving major corporate tax relief is that Democrats would never agree to such a move, and indeed it’s not clear that even conservatives could in good conscience support a measure that would tie a giant tax cut for the wealthy to a regressive carbon tax that hits the poor the hardest.

Kleinbard concedes in his WSJ article that Republicans and Democrats agree that the current tax code is broken. There’s no need to “fix it” by adding in a giant new tax on energy and transportation, which is what a carbon tax means in practice. If the political process has produced a crazy tax code with stultifying barriers to savings and investment, why would we trust that same political process to do the “optimal” thing with a giant new carbon tax?