Wednesday on Twitter, the Niskanen Center’s Jerry Taylor shared a recent carbon tax blog post written by his colleague Nader Sobhani, giving it the following caption: “Niskanen’s @nsobhani_smrc walks us through the economic and environmental impacts of @RepCurbelo’s recently introduced carbon tax legislation. In so doing, he demonstrates that the hysterical response coming from the hard right is, well, utterly baseless.”

I don’t know if Taylor would consider those of us at IER to be “hard right,” but I think our responses to the carbon tax bill introduced by Rep. Carlos Curbelo (see: “Concerns with the Curbelo Carbon Tax” by Robert Murphy and “Curbelo Tax Misses the Mark” by yours truly) show that one need not resort to hysterics to take issue with this proposal. In fact, I would argue that judging by the very barometer established by Taylor himself when he charted the course for Niskanen’s climate program one should oppose the Curbelo bill.

In 2015, Taylor made formal his break with mainline free-market thought on climate action, as represented by IER, the Cato Institute (where he previously served as vice president), the Competitive Enterprise Institute, and the Heritage Foundation, with the publication of his “Conservative Case for a Carbon Tax.” In “The Conservative Case,” Taylor delivers a multi-faceted argument for pricing carbon that he hopes will appeal to the sort of people affiliated with and influenced by the aforementioned organizations. The paper’s executive summary communicates the crux of Taylor’s perspective:

(T)he risks imposed by climate change are real, and a policy of ignoring those risks and hoping for the best is inconsistent with risk management practices conservatives embrace in other, non-climate contexts. Conservatives should embrace a carbon tax (a much less costly means of reducing greenhouse gas emissions) in return for elimination of EPA regulatory authority over greenhouse gas emissions, abolition of green energy subsidies and regulatory mandates, and offsetting tax cuts to provide for revenue neutrality.

In the main text of the paper, Taylor elaborates on three central points:

(1) The alternative to a carbon tax is cumbersome regulations. A tax can replace these.

(2) Regardless of the alternative, a carbon tax should be pursued as a necessary constraint on emissions.

(3) A revenue neutral carbon tax can simultaneously cut emissions and boost the economy.

Let’s now look at each of these points vis-à-vis the Curbelo bill.

A Tax to Replace Regulations

Taylor’s concerns with onerous, inefficient regulations have clear merit. Thanks to the awkward incorporation of greenhouse gas regulation into the Clean Air Act, in the absence of a legislative solution the federal government will continue to regulate emissions in a multitude of ways. The Curbelo bill would indeed take some steps toward remedying this problem by temporarily limiting EPA’s authority:

Unless specifically authorized in section 202, 211, 213, 231, or this section, if emission of any greenhouse gas is subject to taxation pursuant to any of sections 9902 through 9903 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, the Administrator shall not finalize or enforce any rule limiting such emission under this Act (or impose any requirement on any State to limit such emission) on the basis of the emission’s greenhouse gas effects…The moratoria on the Administrator finalizing or enforcing rules limiting the emission of greenhouse gases in sections 330(a), 330(b), and 211(c)(5) of this Act shall expire on January 1, 2033.

But the measures in the Curbelo bill fall decidedly short of the stringent standard Taylor established in “The Conservative Case”:

Finally, EPA regulatory authority over greenhouse gases should be permanently repealed. If emissions are not declining in a satisfactory manner—or if the climate problem appears even more serious than is presently believed—additional emissions reductions should be secured by increasing the tax, not falling back on command-and-control regulation.

The Curbelo bill provides neither a permanent repeal of authority nor an encompassing one, as the bill maintains the Administrator’s power in a number of areas, including:

(1) to limit the emission of any greenhouse gas because of any adverse impact on health or welfare other than its greenhouse gas effects; (2) in limiting emissions as described in paragraph (1), to consider the collateral benefits of limiting the emissions because of greenhouse gas effects; (3) to limit the emission of any other pollutant that is not a greenhouse gas that the Administrator determines by rule has heat-trapping properties.

A Necessary Constraint on Emissions

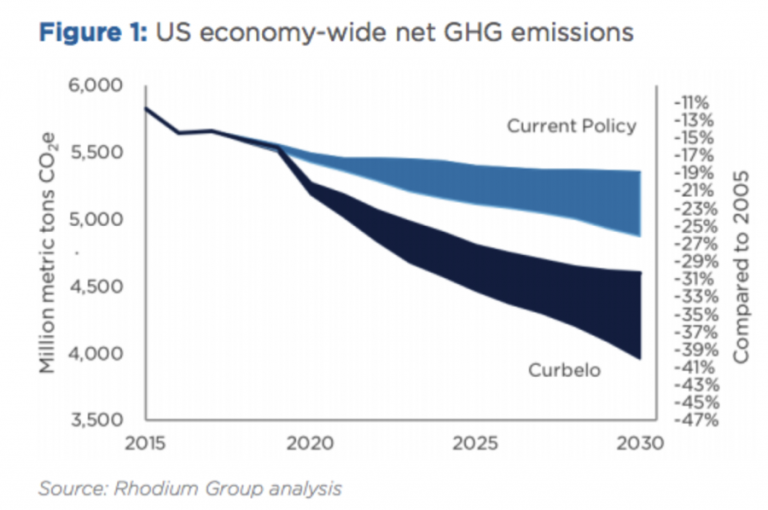

All things being equal, yes, a tax on carbon emissions would, lo and behold, reduce carbon emissions. But the question is, to what effect? Sobhani’s blog post cites the same Columbia analysis that I cited earlier this week, which reports the following:

The Curbelo proposal drives US economy-wide net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions down to 27–32 percent below 2005 levels by 2025 and 30–40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030…The bill represents a departure from current policy, in which emissions are between 18 and 22 percent below 2005 levels in 2025 and 19–26 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

Here’s a visual representation of that downward trajectory via the Rhodium Group:

So, sure, the plan would cut emissions, but, as I wrote previously, the proposed carbon tax would only reduce our emissions by roughly an additional 10 percent from the current trajectory. (A point Sobhani should have made in his blog post.) When we take account of these reductions in the context of the entire world’s emissions, we see how trivial this would indeed be. The United States produces about 15 percent of the world’s GHG emissions right now, but that figure is already shrinking quickly given that U.S. emissions are falling in absolute terms each year while much of the world’s continue to climb. The result is that a deepening of U.S. reductions on this scale will produce a global temperature-rise attenuation of mere hundredths of a degree Celsius. (I’d be remiss not to add that the more sophisticated argument for the carbon tax, rather than direct warming mitigation, is that a tax would incentivize the development of low- and zero-emission technology. And this is, of course, one that the Niskanen Center does make.)

Revenue Neutrality

Taylor’s third prong, that a carbon tax plan need not hamstring the economy, is where the Curbelo bill most obviously goes astray. A revenue-neutral plan would use the incoming stream of money to “fund” tax cuts elsewhere. IER economist Robert Murphy has challenged the premises of revenue neutrality, but regardless of its feasibility, such an approach would at least aspire to commonsense principles of economic prosperity. The Curbelo bill cannot make such a claim; instead of offsetting the costs of the carbon tax with economy-boosting cuts elsewhere, this plan would put more money into the hands of the federal government for spending.

To grasp how crucial to the Niskanen climate charter revenue neutrality was in 2015, consider this passage:

Meeting greenhouse gas emissions targets with a tax rather than with regulation produces revenue that can be used for lump sum rebates or to offset tax cuts elsewhere. Suggestions have been made to use those revenues to offset cuts in the corporate income tax, the capital gains tax, personal income taxes, payroll taxes, and sales taxes. If the carbon tax is less economically harmful than the tax it displaces, a revenue neutral carbon tax is worth embracing even if we leave aside the environmental benefits. Although it is unclear whether a carbon tax swap produces net benefits aside from any consideration of environmental benefits, the important point is that a revenue neutral carbon tax delivers tax cuts.

The only tax that the Curbelo plan would eliminate is the federal tax on gasoline—which would essentially be surpassed by this more comprehensive carbon tax. The cumulative effect of the Curbelo plan is that hundreds of billions of dollars would be taken back out of the economy over the course of the decade, partially nullifying the long-awaited corporate tax reductions enacted last winter. The effect is a slowing of GDP growth by between 0.1 and 0.2 percent, according to the Columbia study.

Conclusion

The atmospheric effects of greenhouse gas emissions and the real world costs they will impose demand serious consideration. Such an approach, however, entails carefully weighing the risks not only of climate change, but also of giving undue power to government and economically harming people in the present.

As a final thought, I’ll share Taylor’s conclusion:

Happily for conservatives, the costs associated with an effective hedge—a revenue neutral carbon tax that displaces the existing command-and-control regulatory regime—would yield a reduction in the size of government, a gain in economic efficiency, and an improvement in conservative political prospects by addressing a problem that worries an overwhelming majority of the American public.

My purpose in highlighting the contrast between the Curbelo bill and the sort of approach pitched in “The Conservative Case” is not to make any accusation of hypocrisy—the Niskanen Center’s stance has evolved over time. Rather, the purpose is to demonstrate that in order to view this proposal unfavorably, one need not even oppose a carbon tax in principle, as IER tends to; one need only apply the litmus test Niskanen’s Jerry Taylor provided just three years ago.

No hysterics necessary.