The George C. Marshall Institute has released a new study from James DeLong outlining what it refers to as “the five circles of Carbon Tax Hell.” The study is very readable and concise (only 34 pages of main text), yet at the same time offers a comprehensive survey of the main problems with a carbon tax. Although DeLong uses colorful metaphors (such as “Carbon Tax Hell”), even so he wades into technical subtleties in the policy debate, and does a good job breaking them down for the layperson. In this post, I’ll summarize the study and focus on some of its gems I haven’t seen elsewhere.

“The Five Circles of Carbon Tax Hell”

DeLong’s “five circles” categorize the problems with a unilateral U.S. federal carbon tax:

1. According to the “consensus” models, it would have almost no impact on global temperatures over the 21st century. Other countries would need to join the anti-carbon-emission program, notably China and India.

2. Projections of modest cost impacts often rely on wishful thinking about the low- or zero-carbon energy sources that would spring into existence to replace our current reliance of coal, oil, and natural gas.

3. The pessimistic assessments of carbon do not fully appreciate the benefits of economic growth made possible by fossil fuels.

4. There are significant problems with the models—both of the climate system and the economy—used to derive the policy recommendations of a carbon tax. It is very dubious to enact trillions of dollars in new taxes on the basis of such computer simulations.

5. There are political roadblocks and other practical problems with implementing the “optimal” carbon tax and achieving the alleged net benefits that the theorists promise.

Hidden Gems in the DeLong Study

The above summary is straightforward enough; the reader can click through to the study to read more. Some of the arguments I have already made on these pages; indeed, DeLong quotes extensively from my own papers, critiquing William Nordhaus’ “DICE” model and the more recent proposals for a “carbon tax swap” deal.

In the remainder of the present post, I want to highlight some key points in DeLong’s paper:

“Bootleggers and Baptists”

DeLong explodes the idea that disinterested academics will neutrally decide on the “optimal” policy, which will then be faithfully implemented by government officials. As DeLong puts it:

A carbon tax is supported by multiple sets of both Bootleggers and Baptists: idealistic environmentalists, crony capitalist subsidy seekers, investment banks in quest of trading profits, government spenders who see a new source of revenue and power, and the recipients of the $280 million in foundation money that goes each year to the field of climate change/energy.

The tax will not be implemented in the politically aseptic world of academic modelers, but in the real world of intense political pressures. Its assumed purity will not survive the onslaught.

The “Bootleggers and Baptists” is a reference to a famous economic analysis of prohibitions on the sale of alcohol, a government policy that was ironically supported by the ideological purists (the tee-totaling Baptists) as well as those breaking the law and thereby earning black-market profits (the bootleggers, including organized crime). DeLong is arguing that powerful corporate interests (such as large investment banks on Wall Street) can benefit from a new carbon scheme, and will therefore support the environmentalists lobbying for such a regime. The standard environmentalist narrative of the little guy who cares about nature versus the polluting fat cats is thus seen as very naïve.

A Unilateral U.S. Carbon Tax Would Have Little Effect on Climate

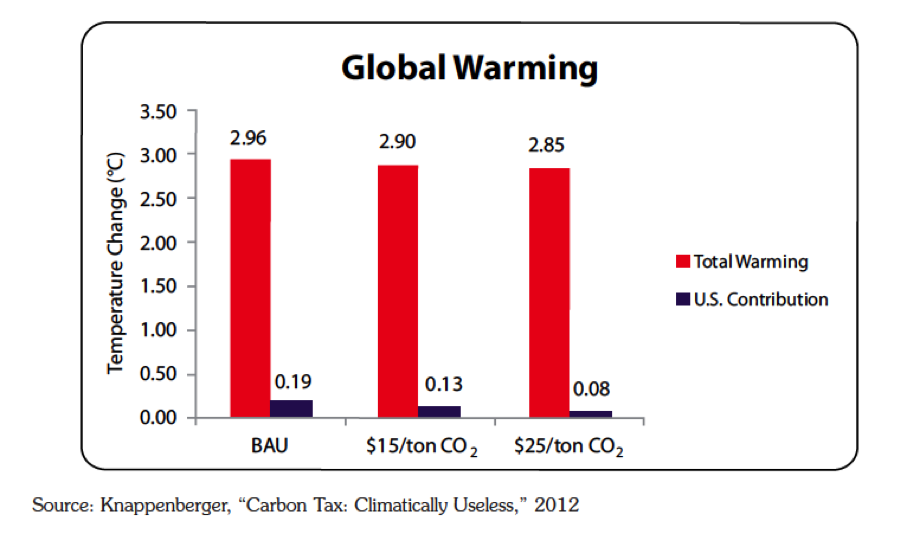

DeLong relies on climate scientist Chip Knappenberger’s work—using the IPCC’s own models—to show the global temperature impact in the 21st century of a unilateral U.S. carbon tax:

In the above diagram, “BAU” stands for “Business As Usual,” meaning the result if there is no carbon tax. The middle section shows that with a $15/ton U.S. tax (holding all else business-as-usual), the world will be six one-hundredths of a degree Celsius cooler than it otherwise would be. The right section shows that with a $25/ton U.S. carbon tax, the world in the year 2100 will be eleven one-hundredths of a degree Celsius cooler than it otherwise would be.

To be sure, the proponents of a carbon tax can argue about the U.S. needing to take leadership in order to persuade other countries to join the carbon regime, etc. Yet it is important to at least point out how crucially the “carbon tax plan” depends on such additional elements. Simply implementing a carbon tax in the United States is not going to solve the problem, even if one is convinced the manmade climate change is a major problem.

A Globally-Enforced, “Optimal” Carbon Tax Is Politically Impossible

To underscore the importance of Knappenberger’s analysis, consider this quotation from the DeLong study, detailing the political problems involved:

Susan Dudley, former head of the Office of Management and Budget Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), is sympathetic to the concept of a “a globally-mirrored, revenue-neutral carbon tax” as the way to discourage GHG emissions.

She assesses the chances of enacting such a tax as zero, because “only a fraction of the political support for climate policy is driven by the supposed climate benefits; most of the impetus comes from the cost side, from groups who expect to be able to profit at the public expense.”

Conclusion

The proponents of a carbon tax like to focus on the natural science claims—looking at carbon dioxide emissions and the relationship with the global climate system. The reason for such an emphasis is that their case completely falls apart once moving from the natural science to the advocacy of political “solutions.”

The only way to even attempt to justify a U.S. federal carbon tax is to come up with some very heroic assumptions about alternative energy sources and the willingness of other governments to follow suit in arresting their own economic development. James DeLong’s new study offers a good survey of the various issues involved, and concludes that a carbon tax has many problems that have not been given sufficient attention in the current policy debate.