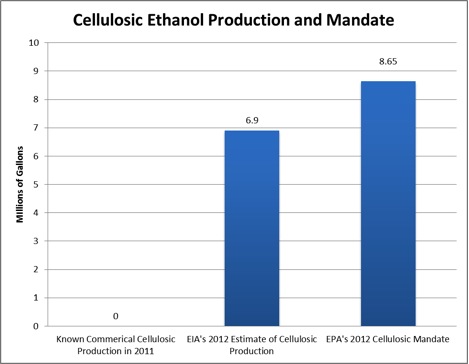

Cellulosic ethanol is not yet commercial, but our politicians and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) are apparently not aware of that fact since they are mandating U.S. refiners to blend it into petroleum products or pay a fine. Refiners will be required to pay about $6.8 million in penalties for not blending enough cellulosic ethanol into gasoline in 2011. Even though cellulosic producers did not sell a single gallon of cellulosic ethanol commercially in 2010 and it is not clear if they sold any cellulosic ethanol in 2011, EPA has mandated that refiners blend even more cellulosic ethanol in 2012. EPA now requires refiners to blend 8.65 million gallons of cellulosic ethanol or pay EPA millions of dollars in fines. The current system rewards EPA for picking an unrealistic number so that EPA can increase the fines it receives. It also means that consumers will be paying higher gasoline prices.

Cellulosic ethanol is ethanol made out of biomass such as wood chips, corn cobs, or so-called energy crops such as switch grass and poplar. Cellulosic ethanol from wood was first produced in Germany in 1898. The Germans developed an industrial process that was also used in two commercial plants in the southeast United States during World War I. The plants closed shortly after World War I due to a drop in lumber production. During World War II, the United States again turned to cellulosic ethanol, but because the technology was still not profitable, the plant closed after the war. Construction of pilot scale cellulosic ethanol plants requires considerable financial support through government grants and subsidies.[i]

When Congress created the cellulosic ethanol mandate, they assigned EPA the task of determining a new mandate each year, if cellulosic producers do not produce the mandated level. Although the agency provides a much lower mandate than what Congress hoped for, EPA’s mandate is far higher than the amount available from pilot plants and higher than the amount suggested by the Energy Information Administration (EIA). The penalties for not blending the prescribed EPA amount are eventually paid by consumers at the pump.

Evolution of Cellulosic Ethanol Mandates

The Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA) contains a renewable fuel standard that mandates the production of ethanol to the level of 36 billion gallons by 2022, where 15 billion gallons is to be corn-based and the remainder is to come from advanced forms of biofuels, including cellulosic ethanol. The advanced biofuel contribution starts at 0.6 billion gallons in 2009 increasing to 1.35 billion gallons in 2011, 2.0 billion gallons in 2012 and eventually to 21.0 billion gallons in 2022. Because cellulosic ethanol was not yet commercial, EPA issued changes to the original act that requires four separate standards including 1.0 billion gallons of biomass-based diesel by 2012 and 16 billion gallons of cellulosic biofuels by 2022, subject to annual assessments that EPA will set each November for the following year.

The original legislation set the goal for motor fuel from cellulose at 250 million gallons for 2011 and 500 million gallons for 2012.[ii] EPA lowered those figures to 6.6 million gallons for 2011 and 8.65 million gallons for 2012, just a small fraction of the original numbers (about 2 percent), but an incredibly large amount when the cellulosic biofuel does not exist commercially.

The Clean Air Act requires the EIA to provide EPA each October with an estimate of the amount of transportation fuel, biomass-based diesel and cellulosic biofuel projected to be available in the following calendar year. EIA’s estimate for 2012 for cellulosic biofuel production is 6.9 million gallons, 20 percent lower than the EPA requirement established for 2012.[iii] To see that even EIA’s lower estimate is high, for 2011, EIA predicted cellulosic biofuel production to be 3.94 million gallons, but “actual sales, if any, are expected to fall well below the estimate” according to the agency.

The State of Cellulosic Ethanol Producers

One reason the mandates cannot be met is that the companies that were expected to produce cellulosic ethanol and that received the first round of subsidies from the government did not make it commercially. About 70 percent of the cellulosic ethanol mandated for 2010 (about 70 million gallons) was expected to come from Alabama-based Cello Energy. However, that projection was made before Cello Energy had built the cellulosic ethanol plant and before the technology was proven to work. In 2009, a jury ruled that Cello Energy lied about how much cellulosic biofuel it could produce and in October 2010, the firm declared bankruptcy.[iv]

A 2011 report by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) concluded that “currently, no commercially viable bio-refineries exist for converting cellulosic biomass to fuel.” The reason, according to the NAS, is because of “the high cost of producing cellulosic biofuels compared with petroleum-based fuels, and uncertainties in future biofuel markets.” According to NAS, even the 2022 target will not be met “unless innovative technologies are developed that unexpectedly improve the cellulosic biofuels production process.” The report also concludes that the renewable fuel standard “may be an ineffective policy for reducing global greenhouse gas emissions,” since the full life cycle of the fuel, including its transport, could result in higher emissions than conventional petroleum.[v]

The federal government under Presidents Bush and Obama has poured at least $1.5 billion of grants and loan subsidies to potential cellulosic producers. Recently, in August 2011, the Obama Administration funded a $510 million program in partnership with the Navy to produce advanced biofuels for the military. In September 2011, the federal government loaned $134 million to Abengoa Bioenergy to build a cellulosic plant in Kansas and the Department of Energy provided POET, which advertises itself as the “world’s largest ethanol producer,” a $105 million loan guarantee for cellulosic biofuels.[vi]

Refiners Must Pay Penalties

Refiners have to purchase waiver credits for failing to comply with the mandate to purchase cellulosic biofuel that does not exist commercially. For 2011, the cost is estimated at $6.8 million, but the amount will not be determined until refiners close their books in February. According to Charles Drevna, president of the National Petrochemical and Refiners Association, the credits cost about $1.20 per gallon.[vii] These costs are passed onto consumers of gasoline and diesel fuel, so the renewable fuels mandate becomes an invisible tax paid at the gas pump. It is just another way for the federal government to tax consumers, and in this case without most of them suspecting it.

Conclusion

Congress subsidized a product (cellulosic biofuel) and mandates its use although that product does not exist and is punishing oil companies for not purchasing the nonexistent product. And the federal government is still subsidizing the industry in the hope that someday it might exist. All along, consumers and taxpayers are paying for the debacle whether at the pump and/or in subsidies and loan guarantees.

As Charles Drevna stated, “Once again, refiners are being ordered to use a substance that is not being produced in commercial quantities—cellulosic ethanol—and are being required to pay millions of dollars for failing to use this nonexistent substance. This makes no sense.”

[i] Wikipedia, Cellulosic ethanol, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cellulosic_ethanol

[ii] New York Times, A fine for not using a biofuel that doesn’t exist, January 9, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/10/business/energy-environment/companies-face-fines-for-not-using-unavailable-biofuel.html?nl=todaysheadlines&emc=tha25

[iii] Ethanol Producer Magazine, EIA issues 2012 ethanol cellulosic biofuel predictions, November 16, 2011, http://ethanolproducer.com/articles/8355/eia-issues-2012-cellulosic-biofuel-predictions

[iv] Wall Street Journal, The Cellulosic Ethanol Debacle, December 14, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204012004577072470158115782.html

[v] National Academy of Sciences, Renewable Fuel Standard Potential Economic and Environmental Effects of U.S. Biofuel Policy, October 2011, http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=13105&page=R1

[vi] Wall Street Journal, The Cellulosic Ethanol Debacle, December 14, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204012004577072470158115782.html

[vii] Wall Street Journal, New Forms of Biofuel Fall Short, December 28, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204296804577125082495631226.html?mod=WSJ_Energy_leftHeadlines