Many companies such as Apple and Google claim that they get their electricity from 100 percent renewable sources. At best, this claim is misleading and deceptive. We cannot find a single instance of a large company actually going “100 percent renewable.” The reality is that as long as these companies are connected to the electric grid, they still get the vast majority of their electricity from conventional sources such as coal, natural gas, and nuclear power, and are therefore not 100 percent renewable.

Who Says They’re “100 Percent Renewable”?

Apple boasts, “every one of our data centers is powered entirely by clean sources such as solar, wind, and geothermal energy.” Google says, “we’re striving to power our company with 100% renewable energy.” A recent BMW commercial introduces “the all-electric BMW i3, built in a wind-powered factory….” The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) actually keeps a list of “100 Percent Green Power Users,” meaning companies that are “using green power to meet 100 percent of their U.S. organization-wide electricity use.” The list currently includes such large companies as Intel, Microsoft, and Kohl’s Department Stores (the three top companies on the list in order of power consumption).

News articles about cities, federal agencies, or even whole countries claiming to make the transition to 100 percent renewable electricity are everywhere. You can find captivating headlines about island nations supposedly going “100 percent renewable.” The EPA includes itself on its Green Power list along with the cities of Washington, DC and Evanston, Illinois. This year, even the Super Bowl at University of Phoenix Stadium was supposedly 100 percent renewable.

Busting the Myth

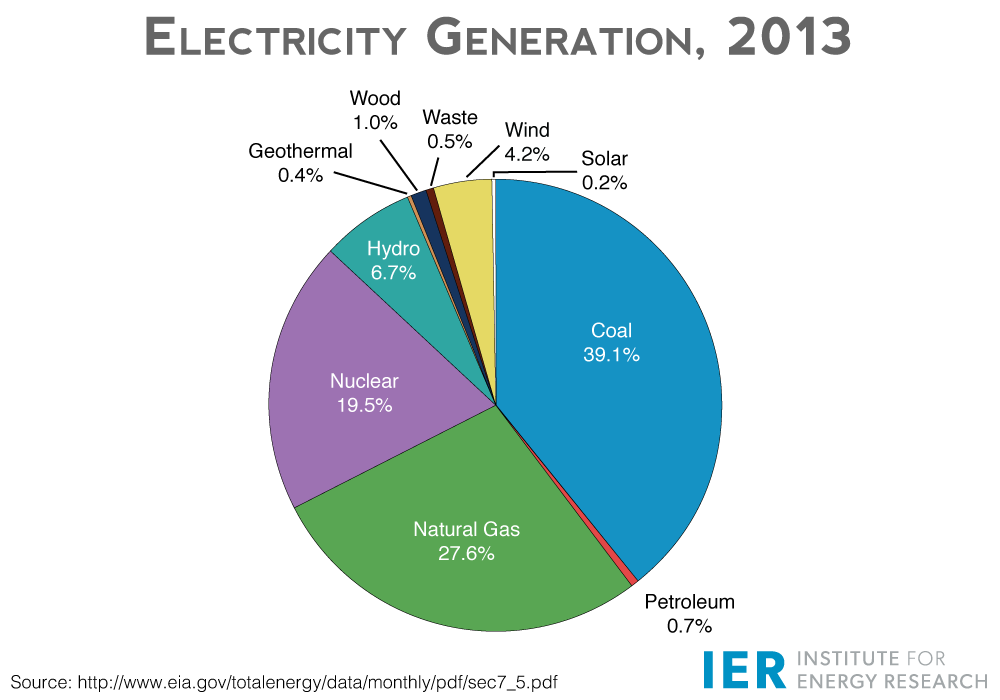

Apple, Google, the Super Bowl, the EPA, and the other members of the “100 percent renewable” club are, in reality, not powered exclusively by renewables. Rather, they are connected to the power grid, which is nowhere near 100 percent renewable. In fact, it’s 86 percent powered by coal, natural gas, and nuclear power. And there’s good reason for that—these technologies offer low-cost, reliable power when and where it is needed. By contrast, wind and solar power combined to produce between only 5 and 6 percent of the electricity in the U.S., and their supply is intermittent and often too far away from population centers to be economic.

The trouble with claiming that anything connected to the power grid is “100 percent renewable” is that, once the electric power is on the grid, there is really no distinction between power that is “renewable” and conventional. Hence it is impossible to selectively use the wind-generated power (or solar power) on the grid and selectively reject coal-generated power (or natural gas, or nuclear power). When companies use power from the grid, they’re using electricity from a mix of hundreds of power plants that use a dozen different technologies over a large, region-wide area.

An analogy can help explain the absurdity of the “100 percent renewable” idea. Imagine someone telling you that the oxygen they breathe is derived 100 percent from eucalyptus trees. Sure, eucalyptus trees produce oxygen, but they are a drop in the bucket compared to everything else producing oxygen, and it’s impossible to know where the specific O2 molecules you’re breathing were actually formed. A few sensible follow-up questions might be: How do you know that? How is that possible? What about all the other production going on in the same system?

The same question applies to the idea of going “100 percent renewable.” Those who claim to be powered 100 percent by renewable sources of electricity are hoping people don’t know how the grid works. In some cases, they buy a certain amount of power from a wind or solar installation (on paper, not necessarily in the physical sense), use a certain amount of power from the grid (not necessarily at the same time as the wind or solar production), and if those amounts are the same, voila! 100 percent renewable. But this is nothing more than an accounting gimmick. When Apple claims it is “now powering 145 of our U.S. retail stores and all of our retail stores in Australia with 100 percent renewable energy,” it certainly does not mean those stores are off the grid. The same goes for its data centers. Apple claims:

All our data centers are powered by 100 percent renewable energy sources, which result in zero greenhouse gas emissions, and we’re committed to keeping it that way. These energy sources include solar, wind, and geothermal power. This renewable energy comes from both onsite sources and energy obtained from local resources.

But as we explain, statements like this neatly gloss over the indispensable nature of the power grid (which the data centers rely on) and all the reliable sources of electricity like coal, natural gas, and nuclear power that keep the grid working every second of every day, rain or shine, wind or calm.

RECs to the Rescue

In fact, some companies that claim to be 100 percent renewable are further muddying the issue by only making a symbolic, indirect purchase of renewables. The implication is that these companies are literally connecting wind turbines and solar panels to their factories to fully power their operations independent of conventional power sources. The reality is much different, and the case of a company or city purchasing so-called Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) from a wind or solar producer illustrates just how misleading these claims can be.

RECs amount to a piece of paper saying the company has “offset” some of the electricity the company buys from conventional sources on the grid—the credits themselves can be bought and sold independent of the renewable energy itself. In other words, a company can buy the “renewable” label and apply it to the grid power it uses in order to call itself green. Thus, many companies that claim to be going 100 percent renewable not only use conventional electricity, but also never directly purchase renewable energy. Instead, they buy a piece of paper they can wave around for PR purposes without having to deal with the consequences of using unreliable wind and solar energy.

Recent actions by IBM illustrate the disconnect between renewable energy credits and renewable energy use. The company recently pledged to get 20 percent of its electricity from renewables by 2020. In a statement, IBM noted it would not be purchasing credits in lieu of actually buying renewables: “We intend to match our purchased renewable electricity directly to our operations as opposed to purchasing renewable energy certificates as offsets, making a clear connection between our purchases and our consumption.” Time will tell. Either way, IBM will still have to contend with the scientific fact that once electricity hits the grid, there is no way of distinguishing between electrons from renewable sources and those from conventional sources.

Why the “100 Percent Renewable” Myth is Harmful

If you’re not relying on accounting tricks, going 100 percent renewable is a wildly uneconomic goal, which is why no one actually does it. A reliable power grid simply cannot run entirely on wind and solar power. Even the isolated island nations that claim to be 100 percent renewable still have reliable diesel generators on hand to meet electricity demand when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining (which can be quite often). Some also have large, expensive arrays of batteries to help smooth out the intermittent production from wind and solar facilities.

Why can’t renewables compete with conventional sources now?

Google says it wants to run on 100 percent renewable energy, but it took just four short years for Google to abandon its own flagship renewables program. Two members of Google’s “RE<C” team (RE<C stands for Renewable Energy less than Coal, in price) recently published their thoughts on the program, which struggled from 2007 to 2011 to find an economic way to produce renewable energy. The researchers concluded that current renewable technologies like wind and solar “simply won’t work”:

Google’s boldest energy move was an effort known as RE<C, which aimed to develop renewable energy sources that would generate electricity more cheaply than coal-fired power plants do. The company announced that Google would help promising technologies mature by investing in start-ups and conducting its own internal R&D. Its aspirational goal: to produce a gigawatt of renewable power more cheaply than a coal-fired plant could, and to achieve this in years, not decades.

Unfortunately, not every Google moon shot leaves Earth orbit.

It may not be surprising that electricity from renewable sources is more expensive than electricity from coal, but certainly we have the technology to go 100 percent renewable if we choose to pay extra for it, right? What is the downside?

The problems with renewables extend far beyond price. Matt Ridley explains the major technological pitfalls of renewable energy in a recent piece for The Wall Street Journal:

The two fundamental problems that renewables face are that they take up too much space and produce too little energy…. To run the U.S. economy entirely on wind would require a wind farm the size of Texas, California and New Mexico combined—backed up by gas on windless days. To power it on wood would require a forest covering two-thirds of the U.S., heavily and continually harvested.

Particularly in the context of the U.S.—with our incredibly reliable and affordable electricity—it makes zero sense to try to run the grid on renewables. The problem with the non-stop headlines about “100 percent renewable” power is that they mislead the public about the feasibility of these technologies. They make it sound like a 100 percent renewable grid is much cheaper, easier, and more desirable than it is.

Lobbyists for the wind and solar industries thrive on such misinformation and half-truths. As a result, these lobbyists have secured billions of dollars worth of subsidies from taxpayers to prop up their expensive, unreliable technologies. The cost of integrating inferior wind and solar technologies imposes a trifecta of harm on American families: it wastes our tax dollars on subsidies, imposes mandates that force us to purchase power we don’t need, and raises our electricity rates.

Conclusion

The “100 percent renewable” claim is misleading and disingenuous. As much as companies like Google and Apple love to tout their purchases of wind and solar power, it’s a good thing for their customers that the companies actually still run on reliable and affordable power from the grid (factories and data centers have no use for dilute, intermittent power). The trouble with propagating the 100 percent renewable myth is that it provides the misinformation the wind and solar lobby needs in order to be successful. It makes these technologies sound practical, which helps lobbyists for the wind and solar industries push for subsidies and mandates that impose expensive and unreliable technologies on the rest of us. Going 100 percent renewable is an outrageously expensive and impractical thing to do—it’s irresponsible to make it sound easy or even desirable.