Since 2009, the Obama Administration has been using the “social cost of carbon” (SCC) in cost-benefit analyses to justify regulations that reduce the use of energy from oil, coal, and natural gas. For the most part, this calculation has flown under the radar, but that changed in June when the Obama administration dramatically increased their estimate of the SCC.

The Obama Administration’s increase of the social cost of carbon, without public comment or scrutiny, has prompted many to look at how the Administration has used the SCC in the past. As we explain here, so far the SCC has been used in nearly 30 rules and can account for over 20 percent of the alleged benefits from some regulations.

What is “Social Cost of Carbon”

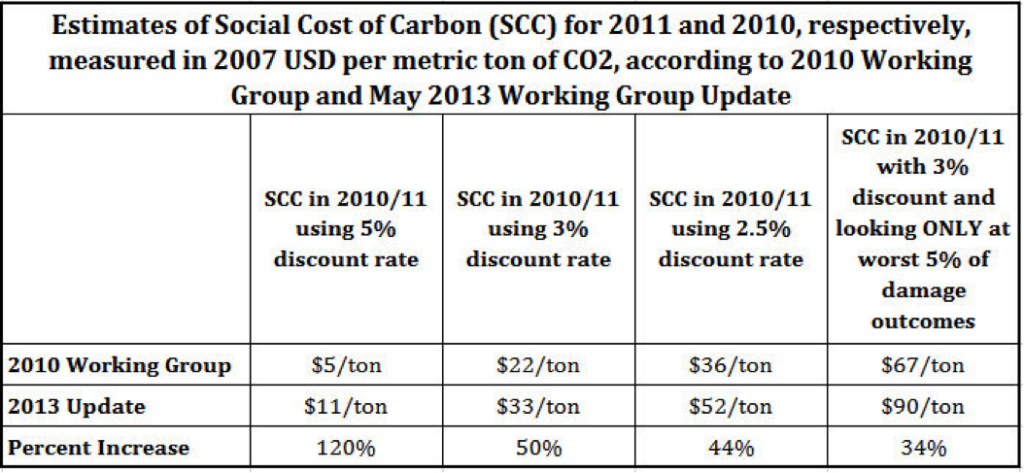

The social cost of carbon is the present-value of projected future net damages from emitting an additional unit (a ton, say) of carbon into the atmosphere. When the federal government started using the social cost of carbon, the amount varied greatly from $0 a ton to $68 a ton.[1] The reason the number varied so greatly is because the calculation requires a large number of assumptions, including the determination of the proper discount rate.

In 2010, the Office of management and budget convened the Interagency Working Group to harmonize the use of the social cost of carbon across the federal government. This Interagency Working Group estimated the social cost of carbon to be $5 a ton at a 5 percent discount rate and $36 a ton at a 2.5 percent discount rate.

In 2013, without public notice or comment and in the appendix to a rule to regulate microwave ovens in standby mode, the Obama Administration dramatically increased their estimate of the social cost of carbon to $11 a ton at a 5 percent discount rate and $52 a ton at a 2.5 percent discount rate. For more information on this increase, here is IER’s Bob Murphy’s explanation.

Source: http:// https://www.instituteforenergyresearch.org/2013/06/06/white-house-revises-dubious-social-cost-of-carbon/

Source: http:// https://www.instituteforenergyresearch.org/2013/06/06/white-house-revises-dubious-social-cost-of-carbon/The Use of the Social Cost of Carbon So Far

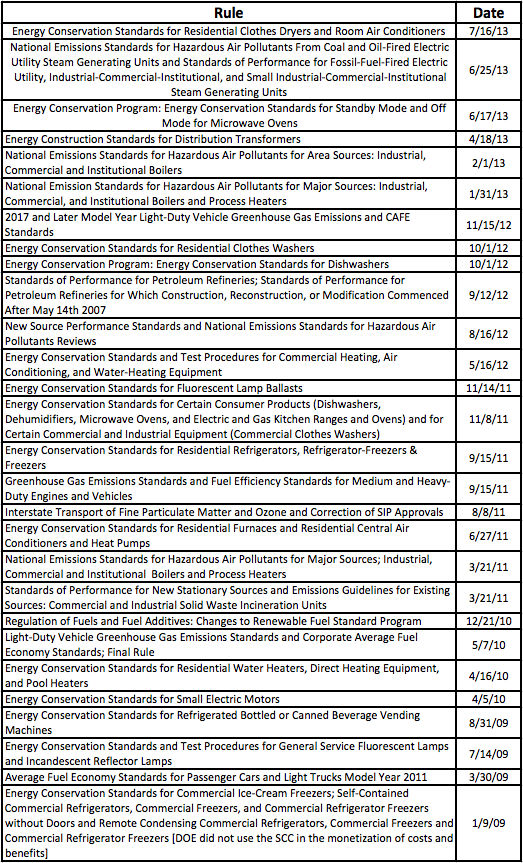

While increasing the social cost of carbon will make it easier for the Obama Administration to justify more expensive rules in the future, they have already used the social cost of carbon calculations in cost-benefit analyses in nearly 30 regulations. Here is the list of regulations that have used the social cost of carbon:

The Impact of the Social Cost of Carbon On Cost Benefit Analyses Before and After the 2013 Increase

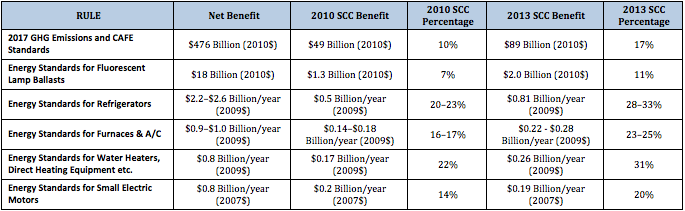

The following table shows the impact of the social cost of carbon on various rules. Prior to the 2013 update, the social cost of carbon contributed just over 20 percent of the net benefits of some regulations. But with the increase, the alleged net benefits jump to over 30 percent in some cases. It’s also important to consider the magnitude of the change in terms of alleged benefits from the social cost of carbon itself. Using the 2010 social cost of carbon, the 2017 CAFE standard generates $49 billion in benefits because of reductions in carbon dioxide emissions, but using the 2013 social cost of carbon the benefits to reducing carbon dioxide emissions is now estimated to be $89 billion.

Conclusion

As the tables show, 2010 social cost of carbon calculations were responsible for a maximum of 23 percent of a rule’s total economic benefit, but with the 2013 social cost of carbon, that percentage can increase to 33 percent. In dollar terms the difference can be stark—the social cost of carbon benefits in the 2017 CAFE standards would increase from $49 billion to a whopping $89 billion, an 82 percent increase. Especially troubling is that this increase in social cost of carbon was implemented without any public comment.

Bob Murphy of IER highlighted the potential impact of the social cost of carbon changes and its de facto role as a carbon tax:

“Government agencies will have the ability to use existing regulations in order to effectively tighten the screws on carbon-emitting activities, by claiming that the new measures pass a cost/benefit test. Even if the public will never support an explicit carbon tax, the machinery is being constructed to achieve the same de facto result—except with greater economic inefficiency—without the need for pesky tax bills. And, it is being done largely in backrooms by the political class or their designees, outside of the view of the public, an increasingly worrisome trend in a system designed to protect liberties through open government with checks and balances.”

As President Obama made clear in his speech on climate change, he has no problem furthering his agenda by executive fiat. This increase in the social cost of carbon, without public input or involvement is just another example of the undemocratic nature of the Obama administration’s regulatory agenda.

This post was authored by IER Policy Associate Landon Stevens

[1] See e.g. Jonathan S. Mansur & Eric A. Posner, Climate Regulation and the Limits of Cost-Benefit Analysis, p. 4, August 2010, http://www.law.uchicago.edu/files/file/525-315-jm-eap-climate.pdf.