A new study by NERA Economic Consulting, prepared for the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), documents the economic dangers of a federal carbon tax. The study is very conservative in its assumptions (as I’ll explain below), giving the benefit of the doubt to the proponents of a carbon tax. Even so, there study reaches two conclusions: Either the US government sets a carbon tax low enough so that its economic impacts are simply bad, but not awful, in which case there are few environmental benefits, or the US government sets a carbon tax aggressive enough to meet the emission goals that its proponents want, in which case it is economically devastating.

Either way, the average American household should be alarmed at the prospects of a U.S. carbon tax—and these numbers, to repeat, are very conservative in their estimates of its economic harms. Before implementing a carbon tax, policymakers should be very clear about what its objectives are. Up till now, proponents keep promising the moon: Extra revenues for tax cuts, deficit reduction, and “clean energy” investment, all while saving the earth from climate change! But the new NERA study shows that this is an illusion. By focusing on one or two of these goals, the carbon tax forfeits the others, and in no case does it pass any reasonable cost/benefit test.

The NERA Study’s Two Carbon Tax Scenarios

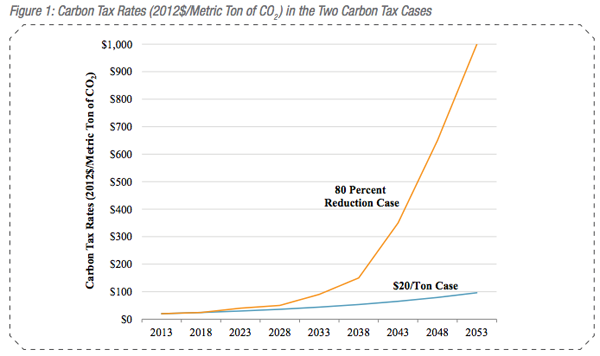

The NERA study looks at two scenarios for assessing the economic impacts of a carbon tax imposed at the federal level in the United States. In the first scenario, it assumes a $20 initial tax levied on each metric ton of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the year 2013, which then increases in inflation-adjusted terms by 4% each year. This scenario lines up with some recent projections conducted by the Congressional Research Service and the Brookings Institution, so it’s a good ballpark of a “modest” carbon tax proposal. Notice that in this scenario, there is a gentle uptick in the carbon tax over time, with little attention being placed on emissions.

The second scenario looks at the carbon tax trajectory that would be necessary to reduce US emissions by 80% relative to 2005 levels, by the year 2053. In other words, the second NERA scenario asks what the carbon tax rates would need to be over the next forty years, in order to achieve an 80% cut in US emissions by the end of the four-decade phase-in period. They picked this specific goal because it too is a popular discussion point, and is often used in discussions of international agreements on climate change policy. The only constraint on the carbon tax rate is a cap placed at $1,000 per metric ton.

The following diagram from the NERA study shows the trajectory of the carbon tax over time, in the two scenarios:

At this point, we should pause and reflect on Figure 1 above. Proponents of a carbon tax like to argue that it will have a “modest” or “negligible” impact on US households, especially in the early years. If they want to argue this way, then they must have in mind the type of carbon tax schedule depicted in the first scenario (the blue line above).

But although the Scenario One approach will raise a lot of money for the government—and will thereby make American households that much poorer in terms of their personal finances—it is nowhere near what the carbon tax “needs” to be, in order to stave off the alleged environmental problems of unrestricted U.S. carbon emissions. The red line above shows the level necessary (in the NERA model) to achieve what the climate alarmists tell us is the barest minimum in cutbacks, to avoid catastrophe.

Thus we see, even at this stage, the rhetorical corner into which the carbon tax proponents have painted themselves. In order to drum up support from citizens for something that will obviously raise gasoline and electricity prices, as well as just about every other price, the carbon tax proponents stress the scientific research on climate change. But then when trying to pooh pooh the negative economic effects of their proposed “solution,” the proponents will talk about a very modest carbon tax that will barely put a dent in the alleged climate problem.

These observations thus far don’t prove whether a carbon tax is a good or a bad idea, but already we see that Americans have not been getting the full story in the standard discussions.

Economic Effects of the Carbon Tax

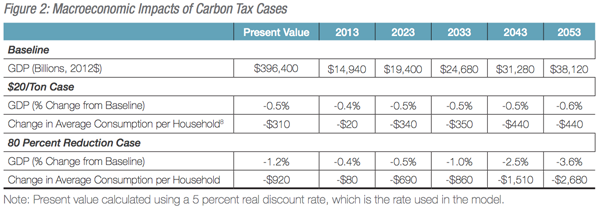

After explaining their two cases, the NERA study summarizes its findings in the following table, where the changes are measured relative to a no-carbon-tax baseline:

Let’s walk through the table above to be sure we understand it. The top line shows the baseline (no carbon tax) forecast of US GDP, in billions of inflation-adjusted dollars. For example, in the year 2033 the NERA study assumes baseline GDP would be $24.68 trillion.

As you move down the table, we see the impact of first the $20 Tax Case, and then the 80% Emission Reduction Tax Case. Since the latter is so much more punitive, it has bigger impacts.

Yet in both cases, we see that the annual impact rises drastically as we move forward in time. For example, the $20 tax case shows only a very modest $20 change in average household consumption in the first year, but this annual impact rises to $350 per household by the year 2033 (i.e. 20 years into the policy). Remember that the NERA study assumes—as do other studies and proposals—that the initially modest $20/metric ton CO2 tax rises steadily over time, which is why the damages increase over time.

In contrast, the 80% Reduction case shows a far more devastating impact. By the final year of implementation (2053), when the carbon tax has hit the ceiling of $1,000 per metric ton, the annual impact on the average household will be a reduction of $2,680—in that year alone. Overall US GDP will be a full 3.6% below what it otherwise would have been, in the absence of a carbon tax.

This is an incredible hit to economic growth. Consider that since the official “recovery” began, there have only been two quarters where US real GDP has grown at more than a 3.6% rate. Thus, NERA’s projected impacts in the second scenario eventually have the carbon tax lopping off more than an entire year’s worth of what would otherwise be considered great economic growth.

Because the impacts ramp up over time, the way to summarize in a “snapshot” the full long-term effects is to compute the “present discounted value.” This involves summing up near-term and long-term outcomes, but discounting future values at a 5% annualized rate. (It’s the same procedure used to calculate the current market value of a bond offering a stream of payments over the years, for example.) With this approach, the NERA study summarizes the $20 Tax Scenario as reducing average household consumption by $310 per year, while the 80% Emission Reduction scenario involves a near-tripling of the damages to $920 per household in an “average” year under the tax.

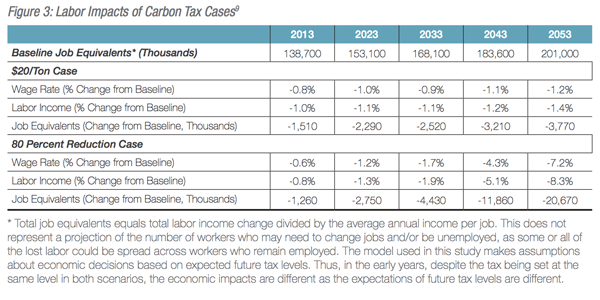

In a similar vein, the NERA study forecasts the carbon tax scenarios on the labor market:

Thus we see, for example, that the more aggressive carbon tax scenario implies a long-run average worker income loss of the equivalent of 1.26 million full-time jobs, while in year 2053 (when the carbon tax reaches its peak) the impact is a staggering hit to worker income of 20.67 million jobs.

It is careful to note that the carbon tax will not permanently “destroy jobs” in the sense that these people will be unable to find work. So long as the government doesn’t tinker with price controls (as President Obama wants to do with low-skill workers with his minimum wage proposals), then after the dust settles from a new carbon tax, workers can find niches in the economy. But the point is, the carbon tax imposes artificial constraints and makes workers less productive. Therefore, even though they can eventually find jobs, they will earn a lower wage or salary than they would have, in the baseline (no carbon tax) case. The “job equivalent” numbers in the table above are quantifying this reduction in total labor income, in terms of how much a full-time worker earns.

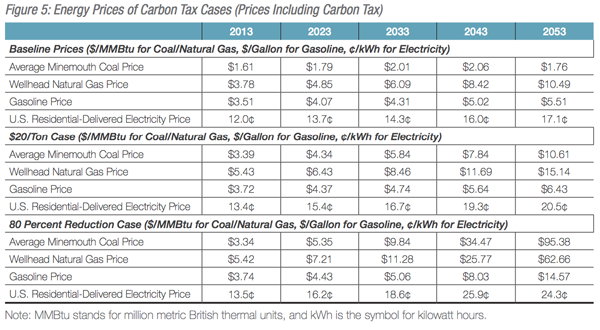

Finally, consider the effect of the two carbon tax scenarios on various energy prices:

In particular, the 80% reduction case shows drastic increases in electricity and gasoline prices in the coming decades, should the US government seriously try to meet the emission reduction targets that many groups are proposing as “sensible climate policy.” By 2053, the NERA study anticipates residential electricity prices having risen 42 percent relative to the baseline, and gasoline pries at a whopping $14.57 per gallon (compared with $5.51 in the no-tax baseline, because of rising crude market prices).

And of course, if someone is interested in the coal industry—forget about it. The price of coal in the high-tax scenario eventually ends up being 54 times higher than it would be without the carbon tax. Such a punitive tax rate will obviously destroy the coal industry, which after all is one of the stated objectives for those who want to drastically reduce US emissions.

The NERA Study Is Very Conservative In Its Projections

The NERA study is very precise and clearly lays out its assumptions; its authors are good economists. However, I would argue that its results are too conservative in their projections of the harms of a carbon tax.

The most obvious reason is that the NERA study assumes the carbon tax receipts will be used to either (a) reduce the federal deficit from what it otherwise would have been, holding spending constant and/or (b) reduce other taxes. In terms of supply-side economic analysis, given that there is going to be a new carbon tax, then the very best things one could do with the revenues is use them to cut other tax rates and/or to make the deficit smaller, so that the government doesn’t siphon off as much from the capital markets away from private investment.

In other words, NERA’s projections of economic outcomes under the two carbon tax scenarios has the government behaving very responsibly, doing just what a free-market economist would want, given that it was imposing a carbon tax.

In reality, of course, the government won’t keep its spending trajectory the same, (for reasons I explain here) in the presence of hundreds of billions of new annual revenue in the modest scenario, and even trillions of dollars in new revenue in the aggressive case. Specifically, the NERA projections show that the 80% Emission Reduction scenario has the federal government taking in $1.8 trillion in inflation-adjusted revenues by the year 2053 from its carbon tax.

Does anybody seriously believe this flood of new revenue won’t lead to higher federal spending than would otherwise be the case? Note that such spending would include any “transition payments” to help poorer households or certain industries adjust to the new carbon tax, which will surely be part of any politically feasible deal.

Conclusion

The new NERA study is a precise work of solid economics that carefully spells out its assumptions and offers nuanced conclusions. It outlines two plausible carbon tax scenarios—one involving “modest” tax rates that won’t significantly alter U.S. carbon dioxide emissions, the other involving very large tax rates that will impose crippling impacts on economic growth, worker income, and energy prices. Yet as ominous as the NERA numbers are, they vastly understate the true economic damage from a carbon tax, because they assume the government will use trillions of dollars (over the years) in new revenue in the most efficient manner possible, which is hardly a plausible assumption.